Ashok Joshi, 69, was convinced cancer would never strike him. For, the Mumbai resident was a passionate runner and had not missed a single city marathon for 16 years. Fitter than his friends, he would flaunt his super-flat abs. But four years ago, his sister, a gynaecologist, succumbed to liposarcoma. Another relative, too, died of cancer. And in December 2018, a routine test revealed that Joshi had prostate cancer. He was “shocked beyond belief”.

A year and a half after his diagnosis, we met Joshi in his one bedroom flat in Mumbai’s upmarket Santacruz. The afternoon sunlight pervaded his cosy home with minimalist decor. For someone who had just come out of surgery and was undergoing radiation and hormone therapy, Joshi looked energetic and happy. “And dashing,” he adds.

On a dark wooden table across from where we sat was a neatly arranged pile of medals—souvenirs of his marathons since 2004. “Running is his oxygen. If he doesn’t hit the road for a day, he becomes glum and sends us all into a spin,” says wife Anita, a retired schoolteacher. “Even cancer could not put the brakes on his running. A few times while undergoing radiation, he would run a good 5km from home to the hospital and back. He even did the 42km marathon in the middle of a six-week long radiation therapy without informing the doctors.”

Joshi and Anita got married in 1985. The couple have two children. A former Reserve Bank of India employee, Joshi refers to his first diagnosis of cancer as a false alarm, until six months later when the real one went off. He was asked to see a specialist in urology when the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test, used to screen for prostate cancer, as part of Joshi’s yearly routine checkup showed a flare up to level 8. Dr Santoshi Nagaonkar, consultant urologist and robotic surgeon, P.D. Hinduja hospital, Mumbai, suggested an MRI that showed some lesions inside the prostate. In January 2019, a biopsy was done to check if the lesions were malignant. The biopsy came out negative. “At that moment, I was relieved and felt like I was on top of the world,” says Joshi.

But Nagaonkar was not satisfied with the negative biopsy report. “There was something still happening inside his prostate,” he says. “We decided to wait and watch for six months.” In those six months, Joshi got busy with the wedding preparations of his elder son, Abhinav. In July 2019, he also signed up for a full marathon (42km), to be held in January 2020. He did not tell his family as he thought they might discourage him from it. That same month, he repeated his PSA test, which came back with a level of 9. It warranted another biopsy, but it was done differently.

In the conventional way, says Nagaonkar, the biopsy is done from the back. “That is the easiest and convenient way to access the prostate and it is the commonest area where the cancer rises from (in 85 per cent cases),” he says. “But in about 10-15 per cent of the [cases], cancers are seen on the front part, too. Hence, the second time we did the transperineal biopsy, where we targeted the prostate from the front and the back and below the testicles. That biopsy result came back positive.”

Joshi’s cancer was moderately aggressive, but fortunately had not spread to any other organs except to the seminal vesicle (a pair of glands found in the male pelvis that secrete a fluid that partly composes the semen). But Nagaonkar told the family that the cancer could spread in no time, and therefore the prostate would have to be removed. Since Joshi’s cancer was in a potentially curable stage, he had the option of either going for surgery followed by radiotherapy, if needed, or just radiotherapy. “Surgery was the only way I wanted because I had heard that radiotherapy had several side-effects,” says Joshi. “My main concern was that I did not want urinary incontinence post surgery.”

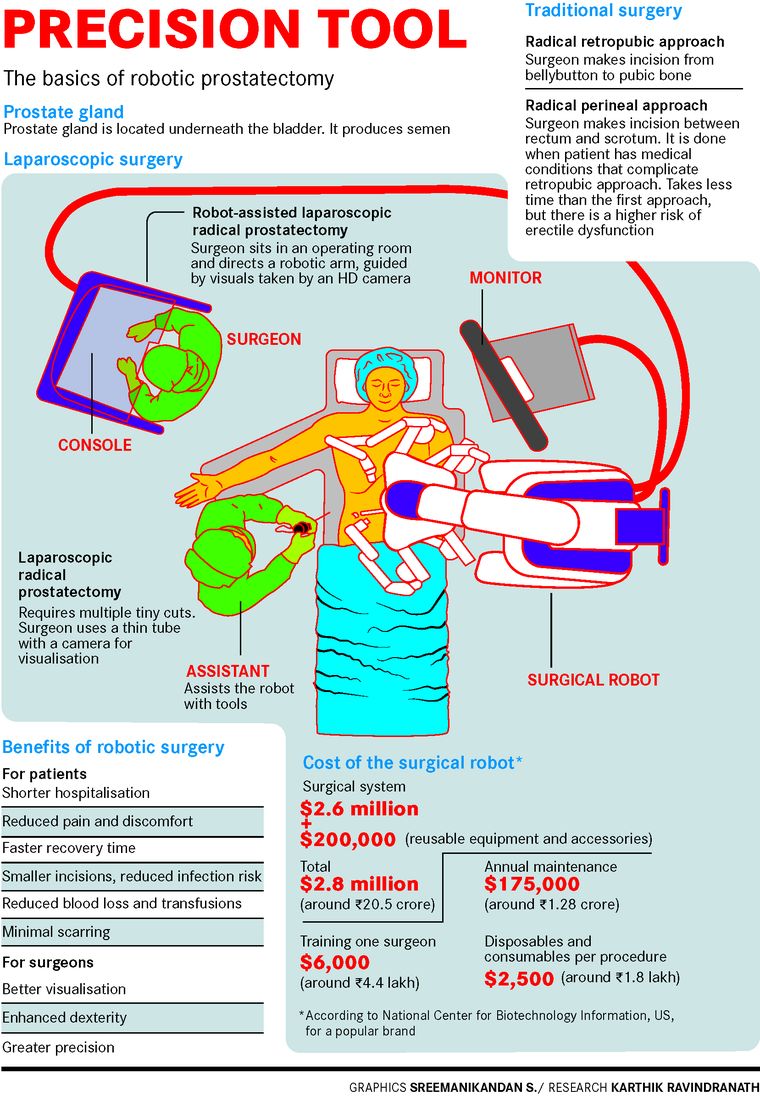

Uttarakhand-born Joshi opted for robotic prostatectomy or robot-assisted surgery. “The doctor works in tandem with the fine precision skills of a robot, making four tiny incisions as against the traditional open prostatectomy in which a single six-inch cut is made for the surgeon to put his hands inside the pelvis area to remove the prostate,” says Joshi. “The traditional method could lead to blood loss of almost a litre, chances of developing infections and requirement of pain relief medications. I just wanted to avoid all of it.”

In robotic prostatectomy, tiny holes are made with the help of which the cannulae or tiny tubes attached to the arms of a robot enter the pelvic region easily and smoothly. The surgeon, who sits on a console inside the operation theatre, directs the cannulae, which has a 3D camera attached to it, with the help of a joystick. “I feel as if I am literally sitting there inside the patient’s pelvis and operating,” says Nagaonkar. “The imagery is so highly defined and sharp that it is impossible to get that kind of precision and clarity in viewing in traditional surgery. It is a magnified view of ten times, so even the smallest blood vessels and nerves can be identified very easily. During the surgery, I could move the robot’s arms into any nook and corner of Joshi’s body without disturbing any of the minute arteries, veins or even the tiniest blood vessels in the process.” Also, he does not have to worry about hand tremors while doing the robot-assisted surgery. “The time spent is 20 per cent less than that in open surgery,” he says.

The robot that assists Nagaonkar is one without a head, torso and even legs. Called da Vinci Xi, it works only with its hands. Before the surgery begins, the robot is placed close to the operating table with the patient. Of the four arms of the robot, one holds a high-definition camera while three others hold the surgical instruments. After the surgeon makes the small cuts in the abdomen, he moves the master controls on the console to put the camera and the instruments in through the cuts to do the surgery. “The prostate sits inside the pelvis and it is very difficult to access that area. The robot is connected to the patient’s body and it is in total tandem with the surgeon,” says Nagaonkar. “It will not make even a millimetre of a movement without the surgeon’s command. There is an assistant next to the robot who helps the robot do the surgery as well. He or she basically gives the (required) instrument on the command of the robot, indirectly on the surgeon’s command. We are constantly communicating through a microphone and receiver.”

Joshi saw the robot a few days after his surgery and marvelled at the machine that made sure he was able to walk the very next day post the surgery. “I was able to stand up and move a few steps just within 24 hours and was discharged from the hospital on the fourth day,” he says. “I am sure it wouldn’t have been possible had I undergone an open surgery, in which the average time is seven days.” One can get back to an active lifestyle within three days of a robotic prostatectomy because the incisions are minor and do not come in the way of your routine activities, say experts.

When Joshi met Nagaonkar after being discharged from the hospital, he told him that he did not feel like he had a surgery and felt like going for a run in a day or two. He, of course, wanted to practise for the full marathon in January 2020. But even if patients of robotic prostatectomy have a quicker healing time, they cannot take up strenuous activities at least for the first five to six weeks.

Joshi thought the worst was over. But with Joshi’s full tumour in his hands and latest reports on the table, Nagaonkar began discussing with him the possibility of radiotherapy, a procedure that Joshi had earlier refused to get done. “Unfortunately, his tumour showed slightly aggressive features. The gleason score, which tells us what the aggression of cancer is like, was 9,” says Nagaonkar. “So upon seeing the full specimen of the tumour, it turned out that the cancer had already tried to spread through the seminal vesicle. We had all the evidence to suggest that the cancer was contained inside the prostate but he still had high-risk factors. I warned him that he will need radiation treatment along with this. He was not very convinced.”

The doctors, therefore, first started him on hormone therapy that eliminates any hidden cancer cells that float inside the body but do not find a place to latch on. This was then followed by radiation therapy. Hormone therapy injections were very painful, says Joshi. “The medicine takes time to get absorbed, about a week or so,” he says. “The first time they gave me two injections and for the initial three to four days, I could not bend, run or do anything.”

Joshi still has to undergo the PSA test once every three months. He continues to enjoy his scotch, vodka or whisky with his bunch of friends and family twice or thrice a week. But the fear of a relapse haunts him.

“The dictum for cancer is that at least for ten years you cannot say that you have been cured,” says Nagaonkar. “But in the first two-three years, we generally get to know which patients are going to do really well and which won’t. In the next two-three years, I will get to know how Joshi will do. But I am sure if he continues to be physically active and mentally strong and receptive, he will do very well.”

Nagaonkar says that Joshi’s PSA is zero now. “The body has washed out the cancer. PSA-free survival is one thing and cancer-free survival another. So, there is only 20-30 per cent chance of Joshi’s PSA remaining zero for the next ten years, but his lifespan will not get affected and that possibility is close to 50-60 per cent. He will not die of prostate cancer.”

A randomised controlled trial suggests that open surgery for patients with localised prostate cancer and robotic surgery achieve similar results in terms of key quality of life indicators at three months. Nagaonkar says this is, by and large, true. “But patient’s morbidity is reduced substantially,” he says. “There is no difference in cancer control. Both [procedures] do that function equally well. But in years to come we will get to know the long-term results.” Robotic prostatectomy was first performed in 2000 in Europe and then in the United States. Currently 95-98 per cent of surgeries for prostate cancer are done robotically in the US, while in India only a few hospitals are undertaking it owing to the cost of the equipment and the skill set required. “In the last two years, we did 200 surgeries,” says Nagaonkar.

Robotic surgery costs at least Rs1.5 lakh more than the conventional surgery. Joshi’s surgery and five-day hospitalisation cost Rs6 lakh. For Joshi though, what mattered the most was coming out of general anaesthesia safely, taking a few steps around the ward with the catheter in place after the surgery and not feeling depressed. “These were met very fast in the robot-assisted surgery, and I was never once depressed,” says Joshi. “The movements came easily, except for the efforts involved. But there was no pain. I was feeling so good that when they asked me to take one round of the ward, I would take two. I was super charged.”

And the fitness junkie that he is, Joshi has continued with his daily workouts. This, despite the lockdown. With the outdoor access restricted, he took to running inside his spacious home. “I began gradually and started timing myself,” says Joshi, who moved to Pune in March. “I worked out a route that wouldn’t disturb the others and went round and round in a 50m loop. Of course, it is not as demanding as running outside but it still gave me a high.” As the lockdown kept extending, he set himself a target and one day covered 21km. In May, his birth month, he ran a full marathon (42km) inside the house in an impressive time span of 4 hours and 20 minutes. “Now that the lockdown is gradually being lifted, I am getting back to my outdoor fitness routine,” he says. “Fortunately, I have been in good health all this while and have been successful in keeping Covid-19 at bay.”