Photo: Cavan Images/Getty Images

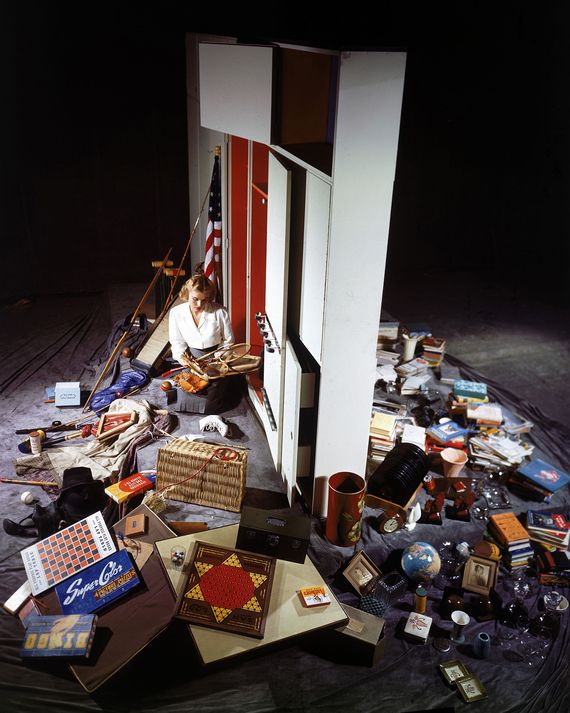

Picnic basket. Badminton racket. Jigsaw puzzles. Cold-weather gear. All these items and hundreds more spill across the floor as a sorrowful blonde clutches more rackets and a baseball glove, a Madonna of the closet. This full-page photograph by Herbert Gehr was staged to accompany a 1945 Life story on the storage wall: the revolutionary new system, designed by architects George Nelson and Henry Wright, that was going to help the American family organize the 10,000 objects they had stashed in attics, on shelves, and in basements. Thirteen feet long and 12 inches deep, the storage wall would separate living room from hallway and house a tenth of the average family’s worldly goods, from sports equipment to stereo system, stationery to board games, behind closed doors.

I always thought of the storage wall as #housegoals, a place for everything and everything in its place. I dreamed of clearing the decks of clutter, from counters to coffee table to bureau top, and seeing only clean space and that Aalto vase every architect owns. As millennial home décor has trended toward the minimalist — by choice and economic necessity — mobile versions of the storage wall, by Ikea and others, have achieved their own level of name recognition. Interiors influencers like Sarah Sherman Samuel have even designed semi-custom doors for Ikea’s Besta in Blush, Agave, and Juniper so their closets and their kid can match. As a mother surrounded on all sides by LEGO and stacks of graphic novels, I knew putting it all away to be largely impossible.

But from the first days of the pandemic, when flour sold out and masks were hard to come by and the (mistaken) powers that be told us to stay inside, my relationship to clutter changed. The already read, the half-finished, the homemade no longer represented failure. On Instagram, I see other people’s stacks of unread books, half-finished painting projects, baking ingredients unearthed from the back of the cupboard and see not unphotogenic messiness but humans, stressed by what’s happening outside, adopting small, manageable challenges at home. With no school, no middle-school musical, no playdates, those LEGOs and graphic novels were looking pretty good. When you spend the majority of your time outside your apartment, at work, at school, at the gym, at restaurants, it isn’t so difficult to keep it picture-perfect. When you and your family are occupying it 24/7, your shelves and cabinets and dressers need to work.

Yes, four of us were packed 24/7 into a house through which we had formerly been accustomed to come and go on our own schedules. Yes, my family needed work space and Zoom backgrounds and room for Tae Kwon Do forms and enough plates and glasses for four times three meals a day. Every dish in the cabinet made it to the dishwasher and the sink. Tupperwares of baked goods hung out on the counter. I ordered snacks in bulk and didn’t know where to put them. My seventh-grader adopted the desk in the living room. The gym mat in the basement came upstairs. If I needed another mask, I had a sewing machine in the closet and a bag full of scraps in a drawer. I wanted to pull it all out, not put it away.

According to Jen Howard’s timely new book Clutter: An Untidy History (Belt Publishing), the Victorians invented clutter. “In 19th-century Britain, during Queen Victoria’s rule,” Howard writes, “industrialization, urbanization, and the expansion of empire, together with an uptick in disposable income, put more objects within reach of more people. Mainstream conventions did not encourage those with means to be minimalists.” The Great Exhibition of 1851 in the Crystal Palace, which gathered materials, objects, and technologies from the far reaches of the British Empire, “showed all the goods the world had to offer,” and people began to display their own identity through décor.

The formal rooms described in Dickens’s novels, darkened by drapes and poor air quality, were also filled with furniture — highboys and sideboards and knickknack shelves — the better to display curios and vases and souvenirs and candlesticks and paintings. Howard quotes historian Judith Flanders’s book Inside the Victorian Home: “There were things to cover things, things to hold other things, things that were representations of yet more things,” and remarks dryly, “This could just as easily refer to the organization of life in the age of the Container Store.”

In the Victorian home, most guests would have been admitted only to a formal parlor, with its antimacassars, lowboys, and landscape paintings arranged for maximum show of identity and purchasing power. That selective, curated display was the equivalent of the Instagram shot of your coffee table with just the right books and a hand-thrown mug — a show of personality that could obscure the less photogenic titles, the unopened mail, the cat hair just out of frame. As quarantine forced us to show people our living spaces all the time on Zoom, that selectivity became much harder to manage. Coffee tables got cluttered with laptops and the detritus of meals. Bookshelves could be propped for the camera but also needed to hold work materials, school supplies, board games, and more.

The Great Exhibition also allowed people without the means to travel the opportunity to own souvenirs from other parts of the world. With travel curtailed, I find myself drawn to objects purchased on past trips — the Turkish bowl that holds some jewelry, the Japanese cotton yukata I bought my kids — remembering where and when I purchased them, because I’m here at home rather than on to the next Instagrammable location. I feel happy to see them out, totems of where I’ve been rather than so much clutter. “Cluttering yourself with objects is a form of escapism,” says senior design curator Brendan Cormier of London’s Victoria & Albert Museum.

In May, the V&A launched an online-only project called “Pandemic Objects,” led by Cormier. “During times of pandemic, a host of everyday often-overlooked ‘objects’ … are suddenly charged with new urgency,” read the mission statement. “Toilet paper becomes a symbol of public panic, a forehead thermometer a tool for social control, convention centres become hospitals, while parks become contested public commodities.” Each pandemic object on the site is paired with something from the museum’s collection, which was begun in 1852 to preserve objects shown in the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London and to inspire more ingenuity and industry in the British going forward. Basically, if Victorians invented clutter, the V&A is clutter’s organizer-in-chief.

“Accidentally, quite a lot of things [in “Pandemic Objects”] were Victorian inventions,” Cormier says. “Victoria Park in East End London was the first public park designed and made to address public-health ideals.” Gardening as well as collecting potted plants and “fashioning interior fantasy green spaces” were also popular pastimes during both the late 19th century and the pandemic, when Home Depot runs have replaced bar crawls.

In another time, a windowsill full of potted plants, along with the tools and vessels needed to keep them happy, could easily have counted as clutter. So too would the dusty sewing machine you inherited from your grandmother or, perhaps, bought during an earlier crafting moment. The sewing machine became a mass-market object during the 1860s thanks to hire-purchase plans created by the sewing-machine mogul I.M. Singer. Machines quickly sold out in the U.K. during lockdown as some suddenly found themselves with more time on their hands, and, over time, scrap bags and fat quarters were transformed into masks, still the most effective means of preventing COVID transmission. Abandoned knitting projects and revived sourdough starters also came to seem more like helps and less like hindrances to the perfectly organized closet or pantry.

George Nelson’s room-dividing storage wall, as seen in Life magazine in 1945. Photo: Herbert Gehr/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

If the middle of the 19th century began the process of acquisitiveness, the postwar era in America accelerated it. January 1945, the date of the Life storage-wall story, seems almost too early for clutter anxiety. The war was barely over, the peak of American suburban home building was still years away, the babies had not yet boomed. The storage wall was more of a harbinger of things to come, an early message that, in the prosperous postwar future, croquet and fishing and family game nights were there for the taking.

Howard quotes A Consumers’ Republic, by historian Lizabeth Cohen, on how shopping took on extra-familiar resonance after World War II: “Wherever one looked in the aftermath of war, one found a vision of postwar America where the general good was best served not by frugality or even moderation, but by individuals pursuing personal wants in a flourishing mass consumption marketplace,” Cohen writes. “Private consumption and public benefit, it was widely argued, went hand in hand.”

All those new homeowners were being pushed in two seemingly contradictory directions: (1) buy things to help the country, and (2) keep your new ranch with attached garage spic-and-span. The culture pushed us toward clutter, and in the personal parts of her book, Howard details her own mother’s spiral into the “squalor and chaos” born of “a lifelong compulsion to comfort herself with things.” Howard’s two-year struggle to clean out her mother’s chaotic house is the narrative driving her book, running parallel to the historical, psychological, and ecological histories of stuff.

“If a family ultimately had all the interior walls of its house built as storage walls it could buy all the clothes and gadgets and knickknacks it wanted without running out of space in which to keep all of them,” Life wrote in 1945. The real dream of Nelson and Wright’s vision of tomorrow’s house was the idea that it could be both minimalist and full of stuff.

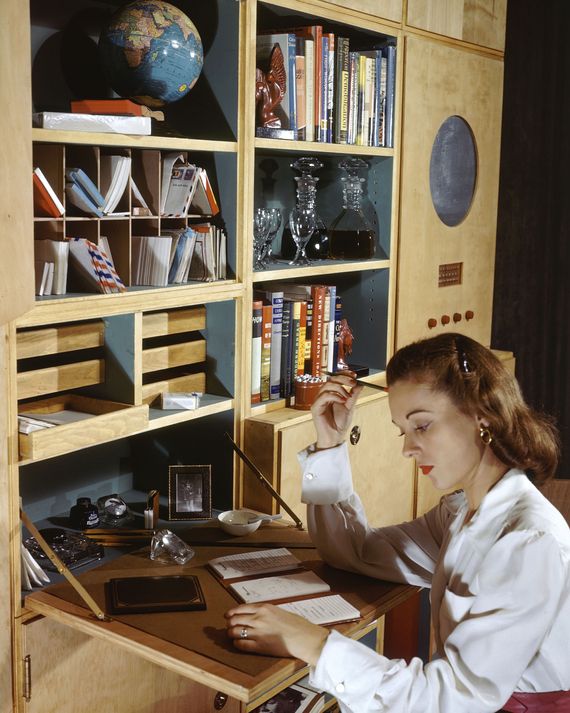

The storage wall in action. Photo: Walter Sanders/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

In the pantheon of American modern houses, the most famous and the most clutter free are for the childless. Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, is often held up as the pinnacle of minimalism, with only a storage wall and a bathroom in a brick cylinder dividing the space. But Johnson was rich enough to simply have other houses in which to store his clutter. The windowless Brick House with a private bedroom, a traditional house in which other people cooked his meals, a shingled house for his boyfriend, a postmodern study with bookshelves, even a renovated farmhouse across the road with a television and stacks of custom puzzles. He didn’t need to keep his board games or even his books in the Glass House, but he did have something to do on evenings at home.

Looking at Life’s sad blonde, I wonder if she’s not mourning the time spent tending the storage wall as much as the 1,000 objects around her. Her energy would be better spent playing one of those games with her kids, not figuring out where to house it, an activity that already skews female. Howard writes, “In most of the families I’m acquainted with, women serve as the organization police. They’re the first responders when a clutter crisis hits.”

That makes this a terrible time to watch the new Netflix series Get Organized With the Home Edit, which launched on September 9 and leaped up the most-watched list. In the series, Nashville-based, Instagram-friendly home organizers Clea Shearer and Joanna Teplin reorganize two homes per episode, one for a celebrity, one for a normie. For those of us who love label-makers and clear-sided bins, it may be soothing to look at all of those color-coded racks, celebrity pantries, and toy baskets, but the show, and the hosts’ Instagram, glosses over the cost of all those storage bins; the work it takes to sort, decant, and clean; the ongoing labor it takes to keep it that way; and the guilt when it all gets out of control again.

With all the additional pressures put on families during quarantine — and the polling that suggests women are doing the majority of the schooling, cooking, and cleaning that was previously hired out — reorganizing the closets and keeping them that way seems like unnecessary pressure. If Container Store consumerism is a cultural construct, we have the ability to change the culture to encourage off-label mixing. The LEGO and the Magna-Tiles should get together and form a beautiful friendship.

“People having greater critical awareness of what a home should be is really positive,” Cormier says. “Capital-D design has been pretty flat and nonreactive during this period, but objects in general, through people using them and repurposing, have shown their richness.” If you are blessed with a house, blessed with souvenirs, blessed with the means to have clutter, enjoy that richness. Don’t be a handmaiden to some image of minimalist perfection. Open the closet and get creative.