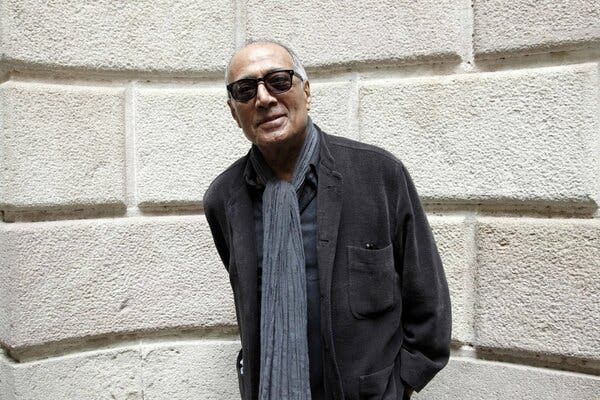

The Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami is widely regarded as one of the great modern filmmakers, but if you discovered him at a particular peak of his international recognition — when he shared the top prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 1997 for “Taste of Cherry” — you might have been baffled. “Taste of Cherry” follows an enigmatic driver who picks up passengers on the outskirts of Tehran. He plans to commit suicide, he says, and needs someone to bury him. For viewers unfamiliar with Kiarostami, watching more than an hour of such conversations was perplexing, even tedious.

Not all of the films of Kiarostami, who died in 2016, were so determinedly minimalist. Still, to follow him over that next decade was to wonder whether he thought all it took to make a movie was a car and a camera. “Ten” (2002) consisted of 10 cab rides. “Five” (2004) had only five apparent shots. Even Roger Ebert, normally one of the most generous critics when it came to introducing readers to international filmmakers, would claim that “Kiarostami is a limited, arid, uninteresting director who inspires reviews much more interesting than his films.”

But with Kiarostami, appearances deceive. In “Five,” something as simple as a shot of waves lapping driftwood invites speculation about whether it was staged. His best work calls attention to the illusion of movies even as he stealthily perpetuates it. And one way to approach his films — which frequently mingle fiction and documentary elements, use nonprofessional actors and gently rap on the fourth wall — is to continually question how they were made. Is this performer simply being or acting for the camera? Was that scene shot extemporaneously, or was it planned in advance?

“Certified Copy”: Stream it on the Criterion Channel; rent or buy it on Amazon, Google Play and iTunes.

“Close-Up”: Stream it on the Criterion Channel or Kanopy; rent or buy it on Amazon or iTunes.

“Certified Copy” (released in the United States in 2011) is an excellent place to start, despite being — on the surface — unusual for the director. A French-Italian-Belgian production, it features a marquee star (Juliette Binoche) and was shot outside Iran, in Tuscany. This time, Kiarostami’s careful framings and lush use of light immediately dispel any notion that he is a minimalist. What’s more, the movie brings his recurring interests to the foreground. Whether the characters are acting is a crucial question here, and the drama pivots on the delicate interplay between the director’s obfuscations and the audience’s willingness to accept them.

The film concerns an author named James Miller (the British opera singer William Shimell) who argues that fakes and forgeries are in their own way valuable — they certify the worth of the original. Shortly before a book event, a woman (Binoche, whose character is never named) gets James to autograph a copy. The woman, who is with her son, is impudent enough to grab a reserved seat, and the boy won’t settle down — odd behavior for guests. And they leave while James is still lecturing. The son thinks his mother is interested in James romantically.

The woman meets James again. They spend the day together, seemingly still strangers, though their rapport cuts oddly deep at times. Then magic happens: While James takes a call outside a cafe, the server, talking to Binoche’s character, mistakes them for husband and wife. And that misperception, or perhaps the influence of the numerous weddings around town, or the pull of the romantic Italian scenery, or the audience’s own conviction that the two simply look like a married couple appears to lead them to behave as if they were.

Could they have been married all along? When I first saw the film, I wandered into a repeat screening almost immediately, convinced I must have missed something. Kiarostami’s sleight of hand is nearly invisible. He signals his debt to the surrealists by casting Jean-Claude Carrière, a longtime screenwriter for Luis Buñuel, as an older husband who gives James advice. And the basic premise is itself a sort of copy, evoking such teetering-couples-on-holiday films as Roberto Rossellini’s “Journey to Italy.”

By the logic of “Certified Copy,” such allusions just affirm the originals’ value. But while the film certainly shows Kiarostami as a worthy peer of those master directors, the themes are fully his own. To see why, look to “Close-Up,” first shown in 1990, which, perhaps even more than “Certified Copy,” asks to what degree audiences are willing to be seduced by a filmmaker’s technique.

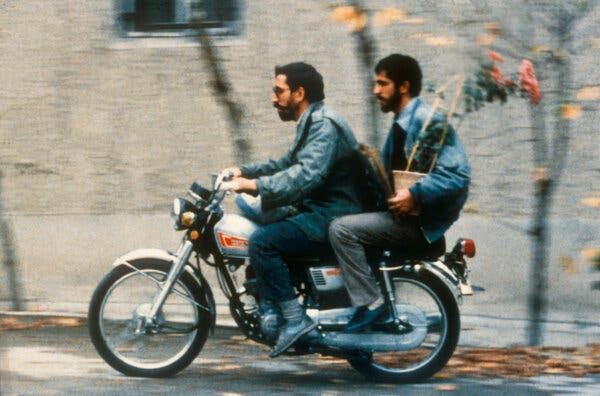

The plot itself concerns being taken in. A blend of dramatization and (seeming) documentary, “Close-Up” centers on a real-life case involving a man named Hossein Sabzian. We are told Sabzian was passing himself off as Mohsen Makhmalbaf, a renowned Iranian filmmaker like Kiarostami. Sabzian and the family he duped — he pretended to be interested in their house as a movie location — appear as themselves.

But “Close-Up” unfolds in at least three overlapping modes, all suspect to some degree. At first it appears to be a dramatized account: It opens with a magazine journalist accompanying the police to Sabzian’s arrest, leading the audience to believe the movie will be about the journalist’s reporting. Then, after the opening credits, “Close-Up” turns into a documentary, with Kiarostami himself interviewing the hoodwinked family and meeting with Sabzian, who is awaiting trial in prison. Then there is Sabzian’s trial, shot on a grainy film stock that distinguishes it from the other documentary parts.

Sabzian, whose remorse may also be acted, says in court that he impersonated Makhmalbaf because he liked the respect that came with being famous; as a poor worker in a print shop, he wasn’t used to having people do what he asked. But it seems that Kiarostami inspires a similar acquiescence in his camera subjects. Before the trial, Kiarostami has a chance to “direct” Sabzian as if they were on a film set: He tells him where the cameras will be and adds, “If there’s anything needing special attention, or that you find questionable, explain it to this camera.”

Kiarostami cuts between dramatized and documentary elements. A flashback reveals that Sabzian’s deception may itself have stemmed from a reflexive judgment (like that of the server in “Certified Copy”). The arrest is shown again from a different perspective. Kiarostami effectively becomes a co-conspirator with Sabzian; he even incorporates one of his fake movie ideas into the coda. The audience, on some level, shares the family’s willingness to be deceived.

Are we actually seeing a repentant criminal or a married couple — or are we simply eager to perceive them in that light? Kiarostami’s surfaces may seem puzzlingly plain, but there’s nothing straightforward about his films.