Technically, Gymnasium, consisting of eight minimalist paintings and a video installation, is Thenjiwe Nkosi’s first solo show.

Since her professional debut in 2009, the artist has been a multifaceted practitioner in the art world. In the 11 years she has been active, Nkosi has had her “hands in many pots”. Between 2010 and 2018, she taught at the universities of the Witwatersrand and of Johannesburg. She has painted countless murals and illustrated book covers. She facilitated workshops and panel discussions, took part in “gang group shows” and spearheaded several curatorial projects.

Taking place at the Johannesburg Stevenson art gallery, the Gymnasium series uses gymnastics as an entry point to comment on how we neglect to humanise each other in performative spaces.

Although her relationship with the gallery was formalised in 2018, when she formed part of the portraiture group show, About Face, Nkosi says one of Stevenson’s directors, Lerato Bereng, would visit her studio to “critically engage” her on her work as it developed. Since her association with Stevenson, Nkosi says “the intensity of the hustle” has changed, because being endorsed by a mainstay institution has allowed her to focus on her work.

Although the partnership allows this, Nkosi sees and misses the value of directly working with or for people. “It’s become more solitary for the time being. That’s something I need to shift.”

Last year Nkosi received the 15th Tollman award: a R100000 grant given to a visual artist who, despite minimal resources, was recognised by the art world. The grant was set up in 2003 by the Tollman family that is behind 25 luxury brands on the African continent including Trafalgar, Contiki Holidays and boutique hotel chain Red Carnation.

“Prizes in art are a tricky thing,” was Nkosi’s sighed response when congratulated on the award.

Other grant recipients include Mawande ka Zenzile, Simphiwe Ndzube, Zanele Muholi, Nicholas Hlobo, Sabelo Mlangeni, Portia Zvavahera and Kemang wa Lehulere. Although the money enabled her to write off debt and focus on her art, Nkosi does not believe in supporting the arts by singling out a talent or basing grants on merit when practitioners receive little to no support from the government.

Instead of a studio-based intervention, Nkosi’s practice oscillates between the studio and social work. She implements the structural changes that she depicts in her art.

“It’s about going outside the [art] market and making work that cannot be consumed economically, work that cannot be commodified,” she explains. Examples of this involve opening up the industry to emerging practitioners and actively making sure that the country’s art education is decolonised.

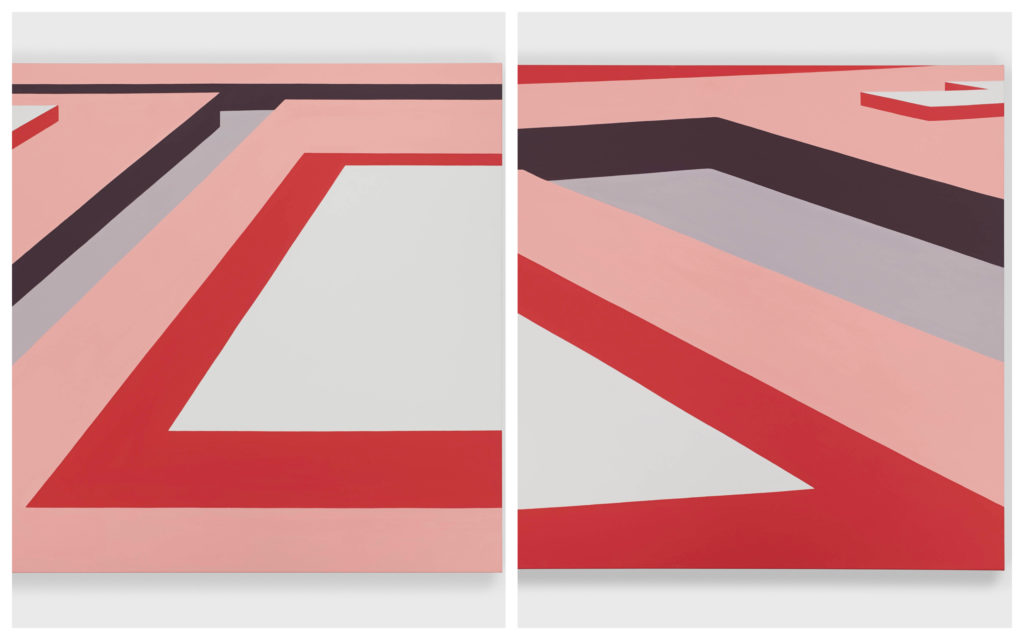

Nkosi’s painting method is rooted in a form of meditation that manifests itself in how her works are free-hand and consist of multiple layers of thin coats of paint. “I think the repetition and painting free-hand gives the work a vibration that wouldn’t be there if I chose to do otherwise. It’s painstaking but it’s meditative,” explains Nkosi. Meditation has “been a grounding practice for me” since she was introduced to it as a teenager practicing Wing Chun Kung Fu.

The layering of paint reinforces colours that could otherwise be too subtle to stand out while the free-hand nature of her painting method makes for a clean and secure finish.

The Gymnasium series was born from an artwork that Nkosi painted in 2012 while she was examining the architectural remnants of apartheid. After coming across a picture of a gymnasium, Nkosi reimagined the scene by recasting the white gymnasts as black characters.

When she returned to the painting last year, its message began to resonate with her as a black artist whose visibility was growing. In an interview with cultural journalism platform, Document Journal, Nkosi explained how the performative nature of gymnastics “translated really well into an experience I was having at this moment. My career is starting to move and I am questioning how I am performing in public.”

Nkosi read what she could on the history of the sport and how it was used as a tool of propaganda, colonisation and white supremacy. In addition to reading and conducting interviews, Nkosi says she spent a lot of her time watching the sport, both live and “hours and hours” of archival footage. “My father always used to say to me, ‘go and see with your own eyes’, and it’s been a powerful piece of advice in making this work,” adds Nkosi.

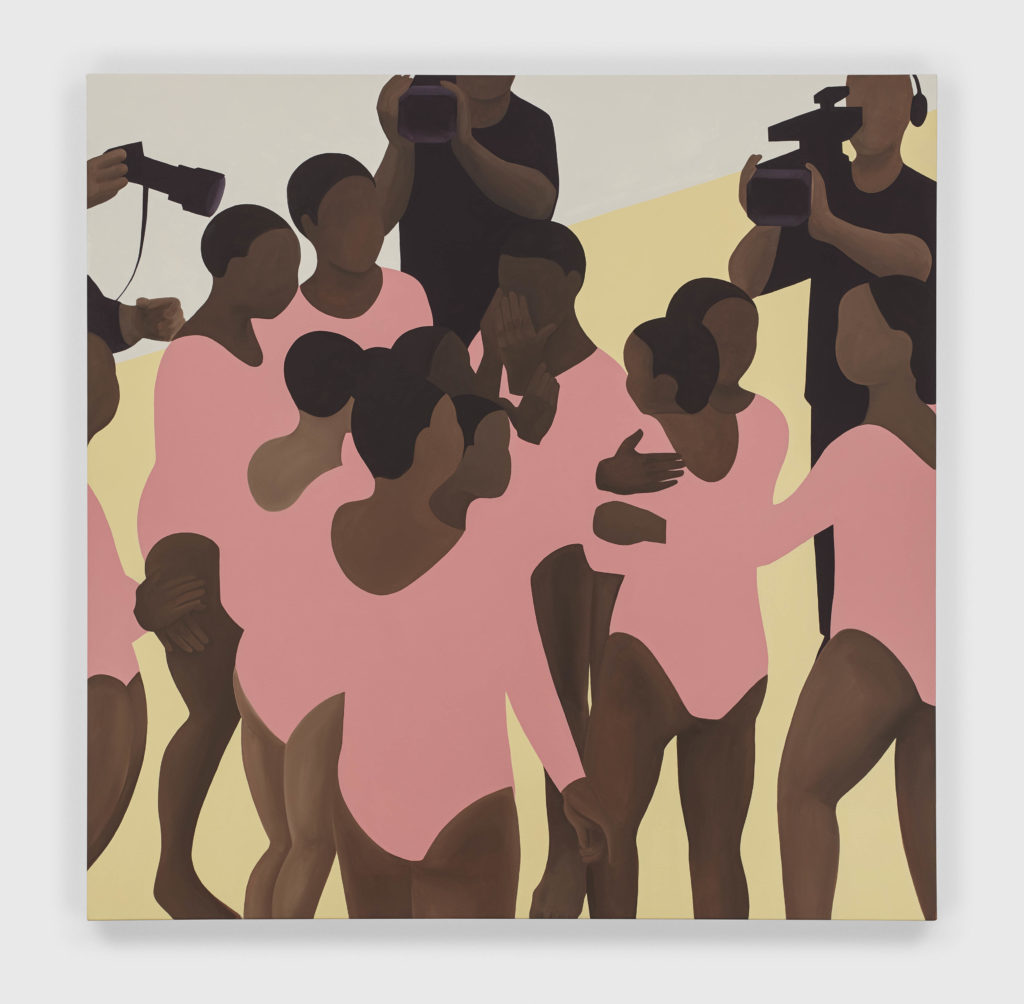

Once she had witnessed several accounts of “the emotional toll and the strength that young gymnasts have to have to be able to excel and continue”, Nkosi began to liken the demanding nature of the sport to the laborious performativity that comes with being a black person in a world that is built on eurocentric, heteronormative, ableist, patriarchal and capitalistic systems that favour whiteness.

In response to this, Nkosi reimagines a world free of the judgments that lead to performativity. As a first step, she ensure that all the characters in Gymnasium were black. With a lot of the work in the series being based on photographs, Nkosi’s interpretations required some manipulation, because she couldn’t find the reference material that she needed. For example, one of the paintings in the series is of an audience. Before painting this, Nkosi searched for an image of an all black and brown crowd watching gymnastics, but had to use an image of white spectators as a starting point, before imagining her loved ones in the white characters’ place.

The characters in Gymnasium exist in, and are limited to, the space where they compete. This is the space where their sense of competence and belonging is determined by their ability to perform according to a static set of specifications and constraints.

The characters are limited to a seemingly constricted space, but Nkosi’s depiction is able to dismantle the athletic objectification that they are subject to. This dismantling sits in the works’ colour palette and the moments that Nkosi chose to paint.

Apart from the character’s rich black and brown skin tones, Gymnasium plays out in soft shades of pink, red, yellow, blue, white and some green. When deciding how to colour Gymnasium, Nkosi took her cues from the sports’ Olympic events. The decision to make use of a muted colour palette was driven by the artist’s need to “reclaim pastel colours”, because Nkosi hopes that Gymnasium is “sensorily calming” and “a space for your eyes to rest”.

The paintings capture the gymnasts as they stretch, hold a pose, prepare equipment, stand on their mark or embrace one another. At no point does the audience get to witness the freeze-frame of a jump, leap, twist or tumble. Instead of painting the performance, Nkosi’s depictions deliberately focus on the scenes that take place before and after the moments of “peak athleticism”, because capturing the overlooked moments makes for a more holistic, more humanising picture of black existence — one that allows us to breathe.

The exhibition opens on March 26 at Stevenson, 46 7th Avenue, Parktown North in Johannesburg. There is no official opening. For information about how and when to see the artwork, keep an eye on stevenson.info

????

????