Filed under:

The new book The Art of Earth Architecture explores one of the oldest—and most ecologically sensitive—building techniques

By Diana Budds

The Tucson Mountain House, in Arizona, is tucked into a secluded desert hillside. The minimalist home has a butterfly roof and large floor-to-ceiling windows, yet it blends in with the terra cotta–colored landscape surrounding it. If you pass by and don’t look closely, you might not even see it. Why? Its architect, Rick Joy, constructed it partly out of earth, a building technique that dates back 8,000 years.

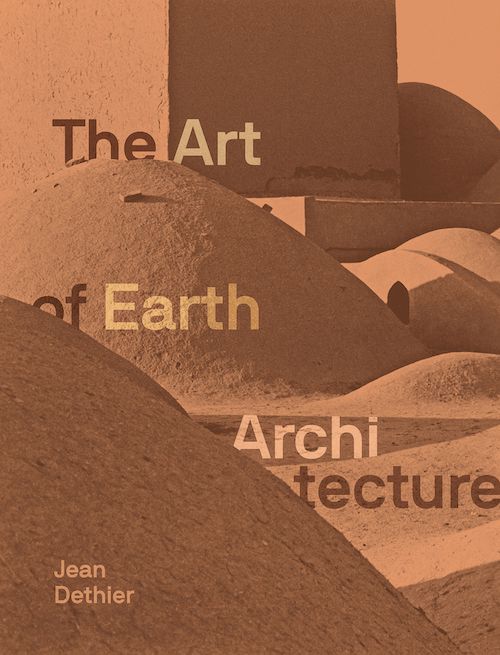

This house is one of 250 buildings in The Art of Earth Architecture: Past, Present, Future, a new book by Jean Dethier and Princeton Architectural Press. Dethier, a curator and historian, has dedicated his 50-plus-year career to exploring architecture made from earthen materials. This book is both an informative global survey of buildings made from the technique—from ancient Egypt to today—and a call to action: Conventional construction is killing the planet, and we need to introduce more ecologically minded techniques into the fold.

“As we face the dangerous and deep crisis related to climate change, we absolutely and urgently need feasible alternatives,” Dethier tells Curbed in an email interview.

Buildings account for a significant proportion of carbon emissions in two ways: The energy they consume to operate (heating, cooling, and lighting) and the energy required to construct them, known as embodied carbon. According to Architecture 2030, a nonprofit organization that is working to reduce carbon emissions, embodied carbon from the building industry accounts for 11 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Concrete, iron, and steel are carbon-intensive materials to produce. The production of cement—which goes into concrete—accounts for eight percent of global carbon emissions. Global steel production accounts for seven to nine percent of carbon emissions.

Reducing the building industry’s reliance on carbon-intensive construction materials is an important step for fighting climate change. Increasingly, the construction industry is looking to natural materials—like mass timber, whose full supply chain might not be as sustainable as proponents argue—as a solution. Experts say rammed earth—which is a focus of Dethier’s book, along with other earthen techniques, like adobe, mud bricks, and cob—is one of the better options because of its structural stability and small carbon footprint.

Traditional rammed earth is made from clay-rich soil, water, and natural stabilizers like animal blood or urine and plant fibers that have been packed down. This technique has been used in the Great Wall of China, in Japanese temples, and the Alhambra palace and fortress. Today, it’s used around the world in luxury homes, like the Tucson house by Rick Joy, offices, shopping centers, places of worship, and more, which are featured in Dethier’s book.

“The optimal new uses of raw earth as a construction material are now increasingly adopted all over the world for three main reasons: It does not need any industrialization process, does not consume fossil energy, and does not emit CO2,” Dethier says. “Housing and buildings appropriately designed to use the local resource of raw earth are providing high climatic comfort, as well as a very pleasant living experience…generating sobriety, economy, beauty, sensuality, harmony with nature and eco-responsibility.”

If the environmental creds of earthen buildings aren’t convincing enough, they’re also incredibly beautiful. Dethier’s book has “art” in the title, after all, and he hopes that it can help “seduce” general readers into becoming advocates for this building technique.

“To efficiently face our world’s ecological crisis, all the citizens have to be informed about realistic ways to adopt a radically new and progressive way of life and consumption,” he says, “including, in priority, how we build and live in our houses, and more broadly in our built environment.”