An ultra-low-cost hearing aid that can be self-assembled could provide an accessible option for seniors with age-related hearing loss who might otherwise go untreated.

Most of us know an older person who needs a hearing aid. Age-related hearing loss is one of the most common chronic health conditions in the world, impacting more than 226 million individuals over the age of 65 globally.

Seniors who live in low-to-middle income countries in parts of Africa and Asia are four times more likely to need a hearing aid than someone living in a Western, developed country such as the US. Despite this, they are much less likely to have access to such a device, with less than 3% of those affected accessing hearing aids in these countries compared with around 20% of those in the West.

“While the costs of the electronic components have reduced substantially, the cost of a hearing aid has risen steadily to the point that it has become unaffordable for the majority of the population,” said Soham Sinha, a Bioengineering Graduate Student at Stanford who worked on the device with Saad Bhamla, a researcher at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Recommended For You

Compared to something like a pair of glasses, worn for age-related sight loss, which can be purchased for under $100, it’s easy to see why hearing aids are out of reach for many people. In the US, hearing aids at the lower end of the scale come in at an average of $1000 and can cost up to $8000 for more deluxe models.

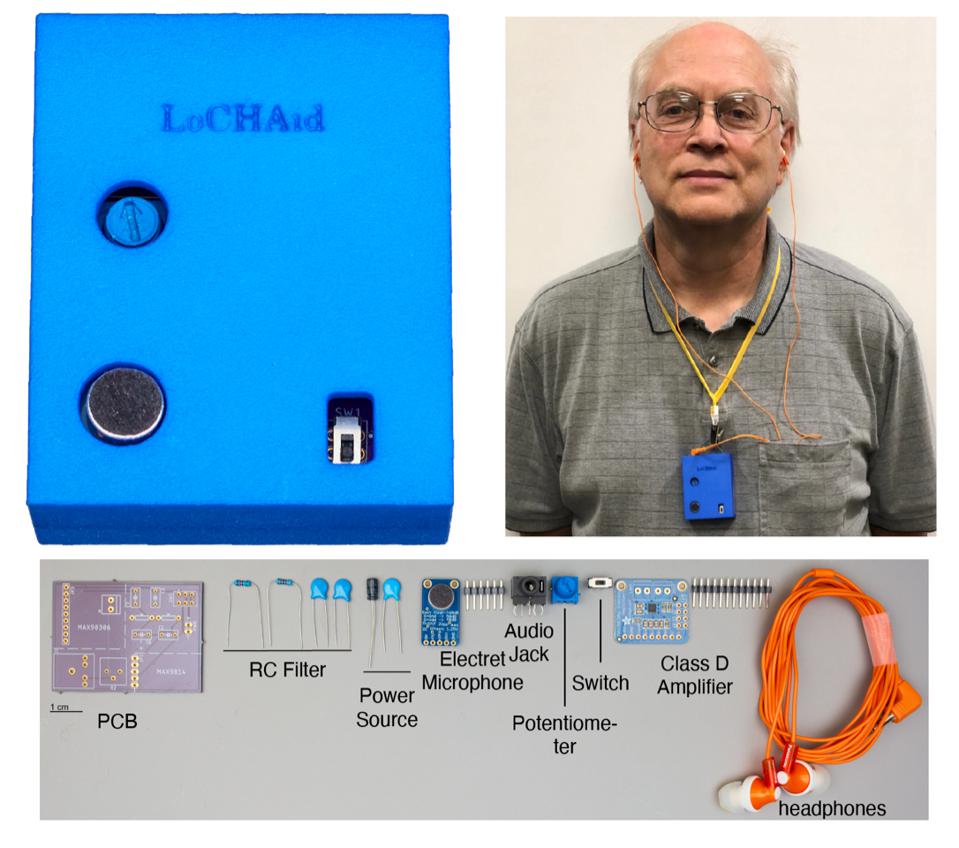

The LoCHAid is built from standard electronic components housed in a 3D-printed shell. The prototype … [+] resembles a wearable music player.

Georgia Institute of Technology

“I was born with hearing loss and didn’t get hearing aids until I was in high school,” said Sinha, who lived in India as a child and worked on the project with Bhamla while a Georgia Tech undergraduate. “This project represented for me an opportunity to learn what I could do to help others who may be in the same situation as me but not have the resources to obtain hearing aids.”

Before designing their device, Sinha and Bhamla looked into why hearing aid prices are currently so high. They discovered a number of reasons for this, which included devices having proprietary software and hardware, a monopoly of companies producing the technology, and a requirement of an audiologist to fit the hearing aid, among others.

There have been attempts to create low-cost solutions in the past, but these “have been found repeatedly to have dangerous electroacoustics which do more harm than good,” says Sinha.

“Hearing aids are currently engineered so that they target the portion of population that can pay for all the bells and whistles, such as, bluetooth capability, fast signal processing and smaller sizes. We wanted to find out the cheapest hearing aid that was still ‘good.’”

With this in mind the researchers produced the LoCHAid with components costing less than $1 when purchased in bulk (10,000 units or more). The device consists of a small circuit board with components that can be soldered on in under 30 minutes using a standard soldering iron. This board is then encased in a durable, 3D printed plastic case that can be hung around the neck, placed in a pocket or worn on the arm and is used with headphones.

To make the device flexible, it was designed to be adaptable to different batteries ranging from two AA batteries to a small lithium ion battery. The latter has the advantage of making the device smaller, but at the cost of lower battery life (72 hours vs 21 days with AA batteries). The hearing aid is also designed to be ‘over-the-counter’ and not require fitting by an audiologist.

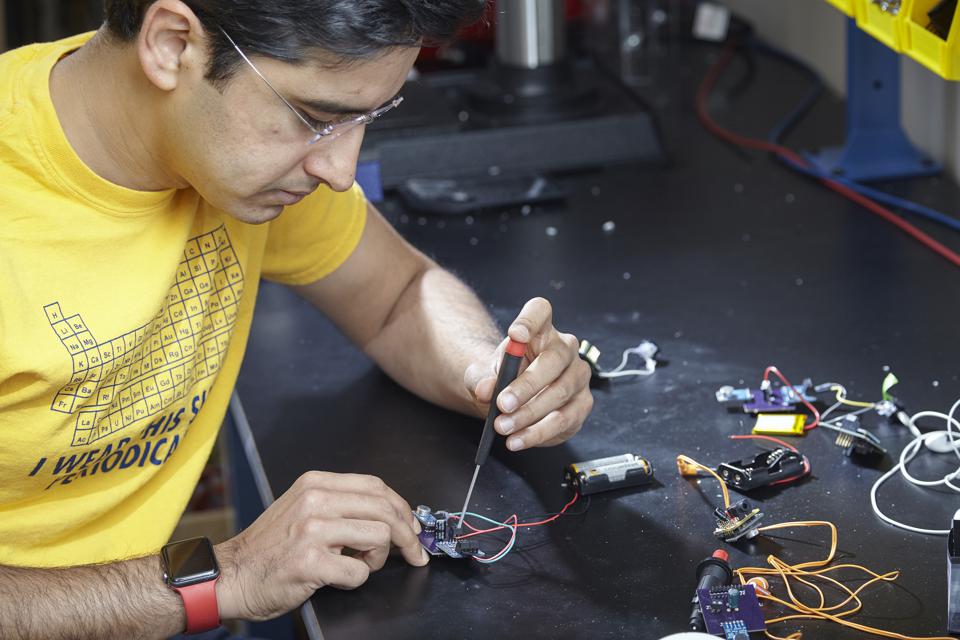

Georgia Tech Assistant Professor M. Saad Bhamla assembles a prototype LoCHAid, an ultra-low-cost … [+] hearing aid built with a 3D-printed case and components that cost less than $1. (Credit: Craig Bromley)

Craig Bromley – Georgia Institute of Technology

“The biggest challenge was validation – a hearing aid isn’t simply an amplification device, it amplifies different amounts at different frequencies,” explained Sinha.

“It’s actually quite easy to make a low-cost amplification device, we were able to create our first prototype in 4 months. However, our entire project took 3 years. The entire remaining time was validation.”

In the end, the engineers managed to design a device that provided a good result for users, although they did have to make some concession to keep the costs down. “We had to compromise on three factors: equivalent input noise — a noise characteristic of the device —programmability, and size,” explained Sinha.

In the same way that off-the-shelf reading glasses are a standard prescription and are often not the most sought-after style, this off-the-shelf hearing aid is not ultra-programmable and is a larger size and more visible than more expensive models.

“An appropriate analogy would be a car – its main purpose to get you to point A and B. However, we have an option to buy luxury vehicles, or second-hand vehicles,” says Sinha.

The team now hopes to refine their prototype further and ideally improve on some of its shortcomings, although they caution that this will drive up the price and may put the device out of reach of older people in less developed countries.

“We designed our hearing aid to be a bit large for ease of manufacturing, and ease of use by geriatric individuals who have trouble with the small components of modern hearing aids… We have a smaller model available… However, the costs rise exponentially with decreasing size, from 96 cents to nearly $8,” explained Sinha

“To introduce programmability, would also drive the cost up couple of times due to the need of implementing both software, and new hardware. Furthermore, it would use up more power, so battery costs would increase. Equivalent input noise, again to use other components specifically for hearing aids, would also drive the price up as they are specifically engineered to have tighter tolerances.”