By Jimmy Stamp • March 10, 2020

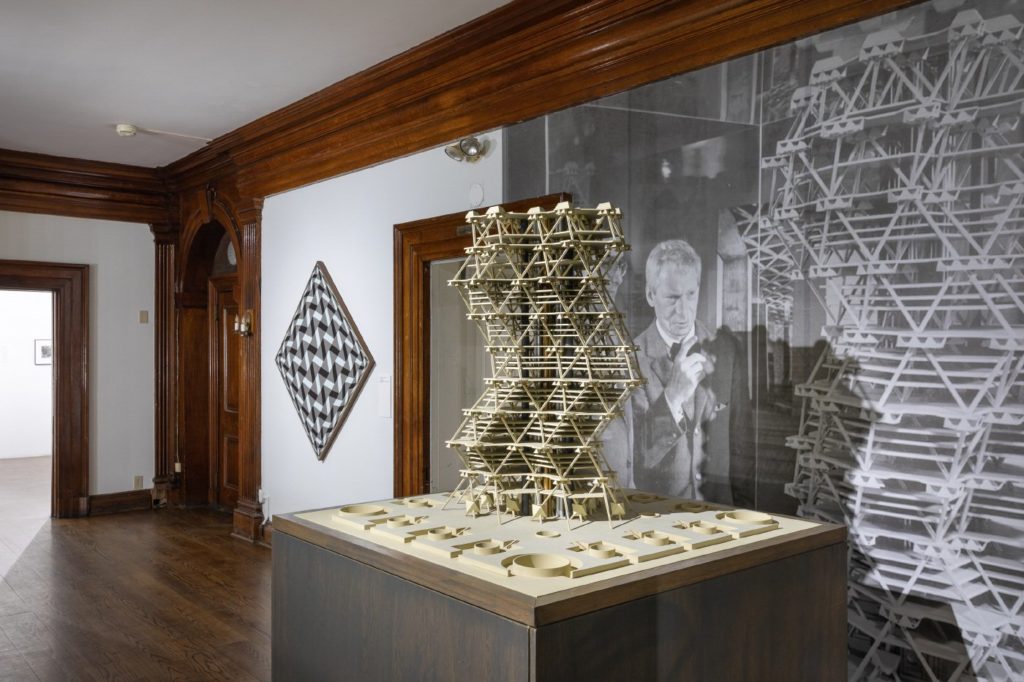

Installation view of Invisible City: Philadelphia and the Vernacular Avant-garde. (Joseph Hu/ Courtesy of University of the Arts)

In the novel Invisible Cities, written by Italo Calvino, we learn of fantastical cities of monumental silver domes, elevated cities of catwalks, and cities made of cities, where residents reinvent themselves with every move. All these cities are, in fact, Venice. In the exhibition Invisible City, curated by Sid Sachs, director of exhibitions at Philadelphia’s University of the Arts, we learn of fanciful cities of roads lined with giant pretzels, cities where twisting towers rise above verdant parkways, and where anthropomorphic puzzle pieces search for connection. All these cities are, in fact, Philadelphia—visions of Philadelphia, anyway, as dreamt up and occasionally realized by avant-garde artists and architects at midcentury.

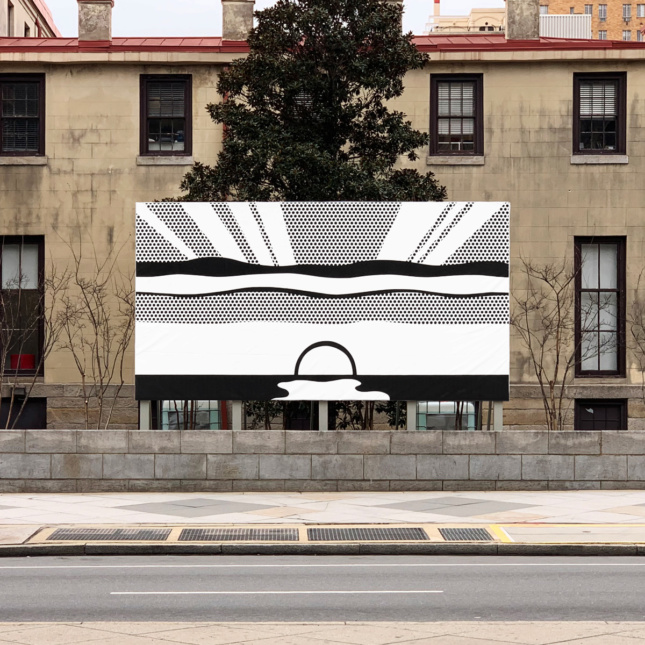

Invisible City spills beyond the confines of gallery walls and into the streets of Philadelphia. (Joseph Hu/ Courtesy of University of the Arts)

Invisible City: Philadelphia and the Vernacular Avant-garde celebrates the City of Brotherly Love’s unique contributions to art and culture from 1956 to 1976, a time when “Philadelphia was fundamental to urban planning, popular music, post-minimalist sculptural installations, and postmodern architecture.” Featuring significant works from the era, the interdisciplinary exhibition spans four venues and an expansive website, with related talks, tours, and capital-H Happenings happening across the city throughout March.

Although the architecture gallery at the Philadelphia Art Alliance will be of particular interest to AN readers, visitors would be remiss to skip past the other venues because Invisible City is best experienced as a whole. The show is an ambitious, sprawling, impressionistic portrait of a creative city at midcentury. It’s beautiful and inspiring, but, like an impressionist portrait, hard to understand what you’re seeing when you get too close.

Different forms of avant-garde and organic furniture are on display. (Joseph Hu/ Courtesy of University of the Arts)

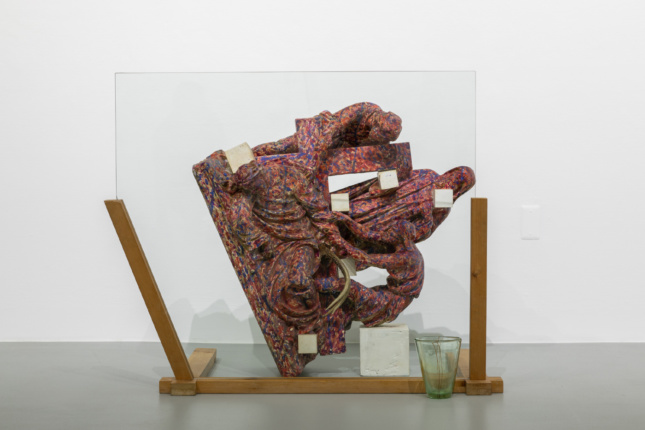

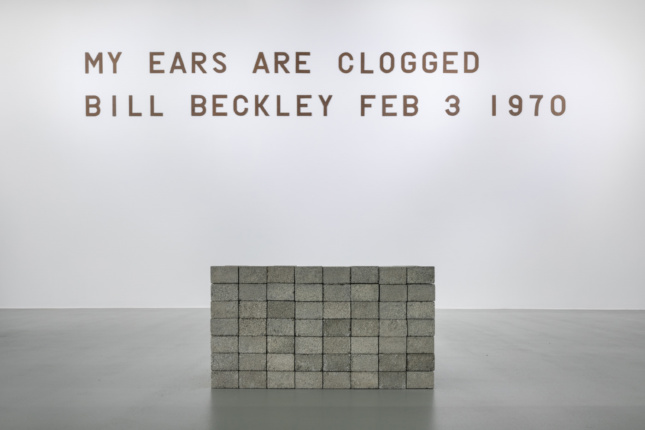

At the Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery, sculptures made from stacked brick, planks of wood, and repurposed lawn ornaments fill the space like a minimalist construction site. The artists on display were clearly influenced by their exposure to Marcel Duchamp’s work at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In another venue, plastic paintings by James Harvard, which look like they were produced in an autobody shop, hang just a few feet away from collages of hypothetical highway roadsigns by Venturi and Rauch with Murphy Levy Wurman—including the aforementioned giant pretzels. It feels like there’s an affinity between these works: the Duchampian interest in the found objects: the Venturian embrace of the ordinary, and the shared interest in witty appropriation, but the show doesn’t make any explicit connection between disciplines or ideas.

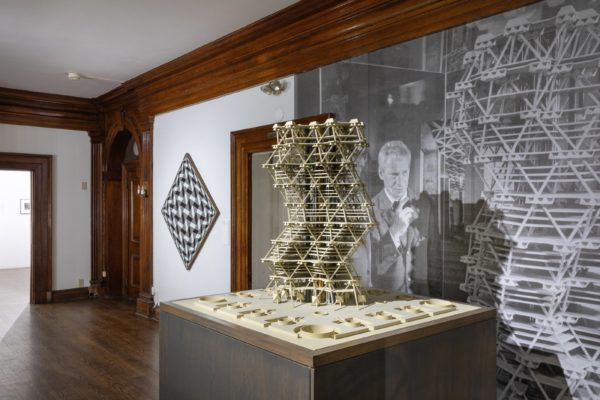

The work of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown is also explored prominently through images, interviews, and models. (Joseph Hu/ Courtesy of University of the Arts)

Things aren’t much clearer at the Philadelphia Art Alliance, where the architecture gallery is bookended by grand visions created for the Bicentennial by Venturi & Rauch and Mitchell/Giurgola. Between these monumental proposals are models, drawings, collages, and ephemera representing works that are more modest in scale, but not in concept: an original basswood model of Anne Tyng’s 1971 Four-Poster Home; a model of Tyng and Louis Kahn’s unbuilt geometric City Tower; hand-corrected pages from Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. It’s an impressive display of some of the best work ever produced by Philadelphia architects. Much of it is familiar. And if it’s not, you’ve got some work to do, because other than name, date, and medium, the exhibit provides no information for most of the work on display.

Were these architects all talking to each other? Were they looking at local artists who were looking at Duchamp? Maybe! The highlight of the show, for me, was discovering some lesser-known talents, like David Slovic and the firm Friday. However, I had to conduct my own research to learn about Friday’s complex, contradictory, and delightfully democratic designs. For any context at all that, you have to go online.

Thankfully, Invisible City’s virtual venue, invisiblecity.uarts.edu, features an extensive chronology and interviews with many of the artists and cultural figures from the era. Whereas the minimal labels and works-behind-glass are cold and distant, the interviews are warm and often personal. Denise Scott Brown shares the story about their fight to preserve South Street, a historic black community that was going to be destroyed for a ring road. Richard Saul Wurman, creator of TED Talks, shares stories about his time as a designer in the offices of Louis Kahn, looking back on his professional experiences with a genuine sense of awe: “Lou changed my life. He taught me you could tell the truth. There were huge penalties…but it was worth it.”

I enjoyed my trip through the Invisible City, despite leaving with more questions than answers: Why is Philadelphia a city where Pop Art and postmodernism germinated but never blossomed? Why is it a city that was home to architects who transformed the discipline, but whose contributions in their own town are surprisingly invisible? “It’s the ultimate question about our city,” says Slovic in his interview. “Why isn’t [Philadelphia] leading the way instead of following?” Why is it an invisible city?

Invisible City: Philadelphia and the Vernacular Avant-garde runs until April 4, 2020.