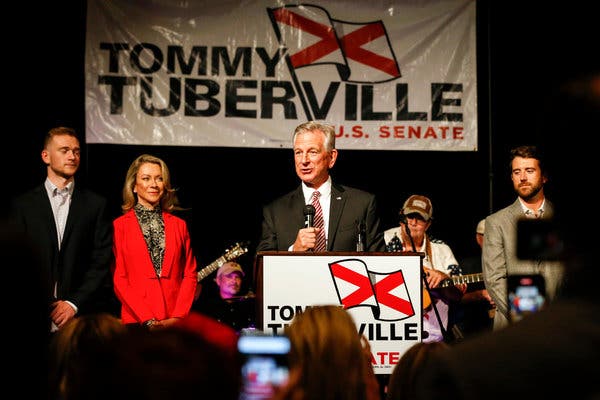

MOBILE, Ala. — On Tuesday evening, addressing supporters and the news media after his runaway victory in the Alabama Senate Republican primary, Tommy Tuberville wasted no time in pivoting toward his general-election opponent this fall, Senator Doug Jones. In Mr. Jones’s Alabama, he said, “You don’t work for the United States of America — you spend your first three years trying to impeach the best president we’ve ever had. And he voted to impeach him!”

As for how Mr. Tuberville will try to frame the race against the Democratic incumbent in the months to come, his message is unlikely to get more complicated than that.

Mr. Tuberville succeeded in his primary campaign against Jeff Sessions in large part by keeping the race simple. His strategy began and ended with President Trump, arguing in a bevy of television ads that a vote for his opponent was a vote against the president. And according to early conversations with his campaign staff, Mr. Tuberville plans to keep Mr. Trump front and center in the general election, reminding voters of moments like Mr. Jones’s vote against Brett M. Kavanaugh, Mr. Trump’s nominee to the Supreme Court, in 2018, and his more recent vote against the president during his impeachment trial.

But one aide for Mr. Tuberville, speaking on the condition of anonymity, added the caveat that the campaign had yet to hold many meetings about its strategy against Mr. Jones. As with most races against Democrats in Alabama, the aide joked, there wasn’t a whole lot to talk about.

But Mr. Jones has managed to navigate the in-between realm where he is both a loyal Democrat and someone who has no problems boasting that working with Republicans and the president is often in Alabama’s interest. In an interview on Wednesday, he name-dropped the state’s senior senator, Richard Shelby, as someone whose record of representing Alabama in Washington he has tried to emulate, and pointed to the 17 bills he sponsored that Mr. Trump has signed into law.

“I have the luxury of telling people in Alabama, ‘Look, I’m going to be for President Trump on issues that are good for Alabama, and I’ve done that,’” Mr. Jones said “But on the other hand, I’m going to speak out when he’s doing things that are not good for Alabama.”

And he said he was betting that voters would appreciate his independence from the president, which is not something they can expect from Mr. Tuberville. Referring to the Republican senators in the South, Mr. Jones said: “They’ve been pretty timid. They wouldn’t speak out. And people take notice of that.”

Even in Alabama, a deeply conservative state where Mr. Trump’s approval rating is regularly the highest of any state among registered voters, a minimalist campaign strategy could undermine even a heavily favored Republican candidate.

For many Republicans here, the wounds of the last Senate race, in 2017 — in which the Republican Roy S. Moore lost a special election, to replace Mr. Sessions, to Mr. Jones after being accused of molesting underage girls — are still fresh. And while virtually every Alabama Republican believes their party will prevail in November, some fear that Mr. Tuberville, a former Auburn University football coach who has never held elected office, is particularly vulnerable to the kind of scrutiny that could make the path more difficult.

If he receives that sort of attention, “then Doug Jones is going to get back in office,” predicted Cody Phillips, a member of the Republican Executive Committee for Baldwin County, east of Mobile. “Because the Democratic Party is going to attack him on all these issues.”

Those issues include questions about Mr. Tuberville’s time at the helm of a hedge fund that ended in charges of financial fraud. Mr. Tuberville’s partner in the venture was sentenced to 10 years in prison; accused of fraud as well, Mr. Tuberville reached a private settlement with investors in 2013, the details of which have not been made public.

But Terry Lathan, the chair of the Alabama Republican Party, said that one factor would still motivate voters above all else.

“It’s pretty simple, actually,” Ms. Lathan said. “Doug Jones only votes with the president 36 percent of the time.”

Mr. Tuberville was able to avoid on-the-spot questions about the hedge fund — about most things, really — throughout the primary race. He rarely held public events or agreed to interviews with reporters, instead focusing his campaign on substantial television ad buys that reiterated his endorsement from Mr. Trump. The Tuberville aide said the campaign would most likely do more news media and public appearances during the general election, but said it would largely depend on whether internal polling suggested they were necessary.

If Mr. Tuberville’s campaign is still lingering in the afterglow of Tuesday’s victory, Mr. Jones and the Alabama Democratic Party have hit the ground running. For Mr. Tuberville’s first morning as the Republican nominee, the senator unleashed a combative Twitter burst, and the state party let loose a torrent of criticism directed at Mr. Tuberville’s political positions and (highly successful, on the whole) football record.

They picked out his loss to Vanderbilt, a perennial underdog, in 2008 while he was the coach at Auburn University, a game that was nationally televised and an embarrassment for the football powerhouse, as well as his 36-0 loss to Alabama that year during the two universities’ annual matchup, known as the Iron Bowl. They also criticized Mr. Tuberville’s treatment, while he was at Auburn, of a player who had been charged with rape.

The morning outburst quickly sent the Alabama Democrats’ Twitter account trending nationally; the group tried to capitalize on the popularity of its tweets by including links to its ActBlue fund-raising page.

Many Democrats and progressive activists celebrated Mr. Jones’s successful 2017 campaign as a teachable moment for the party, offering a template for a way out of the political wilderness in a state that a year earlier had voted for Mr. Trump by nearly 30 percentage points. These Democrats said that if only more candidates took Mr. Jones’s approach, which leaned heavily on turnout among African-American voters, they would surprise themselves with more victories in the Deep South.

But Mr. Jones probably would not have become the first Democrat elected to the Senate from Alabama in a generation were it not for a unique turn of events, above all the fact that many Republicans found his opponent, Mr. Moore, so distasteful that they voted for write-in candidates instead.

And Ms. Lathan, the Alabama Republican chair, was quick to note that an overwhelming number of the state’s Republicans simply hadn’t voted in the election at all.

“If our voters show back up” in November, she said, “we’re unstoppable.” (Mr. Jones, in the interview, noted that in fact Republicans did not show up on Tuesday, when statewide turnout did not even reach 20 percent of registered voters.)

Mr. Jones’s considerable financial advantage in this year’s race is one of the brightest spots for his campaign, and it has allowed him to get in front of the public early with positive ads, which the Republicans have left unanswered and that stand in sharp contrast to the overwhelmingly negative ad war that played out on the Republican side in recent weeks. By one count, the Sessions-Tuberville race had the lowest share of positive ads of any Senate primary in the country.

In one such ad, Mr. Jones speaks tenderly about how George Floyd “cried for his mama” as the police suffocated him in Minneapolis. “As we witnessed his death together,” Mr. Jones says, looking into the camera, “the world changed.”

The Jones campaign appears to have enough money to keep the television ads coming. On Wednesday it said it had raised $2.7 million from the beginning of April through the end of June, and had $8.8 million in cash on hand. The Tuberville campaign, by comparison, had just $448,000 on hand, according to the most recent campaign report it filed, at the end of June.

Mr. Jones has been a prodigious fund-raiser, bringing in more than $18 million over all, among the highest of the Democrats running for Senate this year. That should help cushion him in the likely event that the Democratic Party and its Senate campaign arm, under the guidance of Senator Chuck Schumer of New York, devote few resources to Alabama, choosing instead to boost candidates in states where Mr. Trump is less popular.

“The fact that Schumer’s political operation has not lifted a financial finger for Jones says it all — that he will not be returning next year,” said Scott Reed, the chief political strategist for the Republican-allied United States Chamber of Commerce.

But Mr. Schumer said Wednesday that Republicans underestimated Mr. Jones at their peril. “Never count Doug Jones out,” he said. “The chamber is afraid of anyone who isn’t blindly loyal to their goal of enriching special interests.”

Regardless of Mr. Jones’s prospects or national support, political observers in the state expect the race will heat up quickly, as Mr. Jones begins to aim his advertising efforts at his newly anointed general election opponent’s scant experience in politics, shallow ties to the state and troubled business record.

Palmer Hamilton, a lawyer in Mobile who has supported Alabama Republicans like Mr. Shelby and Mr. Sessions, recalled in an interview how Howell Heflin, the last Democrat to represent the state in the Senate before Mr. Jones, once described Alabama’s merciless brand of politics.

“Heflin used to say, ‘Politics in Alabama is dirty business.’ Pause. ‘When it’s done properly,’” Mr. Hamilton said. “We have a history of hardball politics. Doug and his people understand that. And they don’t plan to go soft on Tuberville.”