After several months of forced inactivity because of the pandemic, New York’s art galleries are back, with a vengeance. Since Labor Day, they have collectively mustered one of the better fall seasons of the last several years, with more to come in the weeks ahead. Yes, there have been changes. Unfortunately, some galleries have closed, while others are being worryingly slow to reopen. Yet fewer have gone missing than seemed likely in March or April. Others have sought new leases on life by relocating from Chelsea to TriBeCa, or from SoHo to the Upper East Side, and so forth.

In the face of the economic unknowns, the collective message from galleries sounds something like: we’re not taking this lying down.

The sense of resurgence is especially tangible in Chelsea, where my running list of shows to see has reached 74. A good number form a fractious conversation about painting.

The differing viewpoints about the medium can be dizzying, ricocheting off each other. They range from Pieter Schoolwerth’s demonically choreographed “Shifted Sims” series at Petzel Gallery — where figures and interiors from the Sims video games, printed on canvas, intersect with mannered applications of paint, forming a disturbing netherworld of social and art-making rituals — to Julian Schnabel’s latest forays into Romantic abstraction at Pace. In them, great flourishes of white and blue unfurl across slightly shaped stretchers with a dusty pink tarp serving as canvas. And they are bookended by shows of crisp new Minimalist paintings from Robert Mangold, and Yoshitomo Nara’s unendingly cute, wide-eyed innocents, brought forth with consummate ease in paint and colored pencil.

Mr. Schoolwerth’s fastidious craft finds some echo in Kyle Dunn’s work at P.P.O.W., where the paintings build on the homoerotic realism of Paul Cadmus and the stylized figuration of Tamara de Lempicka — once-overlooked talents of the 1930s. His beautifully carved wood frames ripple around and sometimes interrupt the images.

At Berry Campbell you can see the all-but-forgotten fusion of Minimalist boldness and Color Field staining that Edward Avesidian achieved in the mid-1960s. And Michael Rosenfeld Gallery has brought together a large, stunning group of Benny Andrews’s portraits primarily from the 1970s and ’80s which have not been seen together before. The psychological realness of Mr. Andrews’s Black subjects contrasts strikingly with the more polemical go-for-the jugular approach of a younger generation exemplified by the strong new paintings in Titus Kaphar’s first show at Gagosian, two blocks away.

Taken together these eight shows, and the four reviewed below — with four more very honorable mentions — demonstrate how completely open painting is right now, how distant are the illusions of dominant styles that once squeezed out all but major players.

Through Oct. 31 at Greene Naftali Gallery, 508 West 26th Street; 212-463-7770, greenenaftaligallery.com.

This may be the most exciting painting show in Chelsea right now. Although Mr. Price has had several promising solos in New York, including at MoMA P.S. 1, and appeared in the last Whitney Biennial, it has a breakout feeling. His scale has expanded, his integration of cartoon-based imagery and painterly improvisation has gained confidence and his ideas are laid out in an abundance of often excellent drawings that fill two small spaces of their own.

Mr. Price, who was born in 1989 in Macon, Ga., and lives in Brooklyn, has a great way with materials, from the crayons and transparent yellow tape that appear in his drawings, to oil paint, which he approaches with a keen sense of color and manages almost always to infuse with fire or light. He has one eye on art history and another on the richness and the stresses of Black life. Even the small paintings are like big stages where human and painterly dramas intersect. Sometimes this turns slightly mythic, as in the painting “A breeze filled with determination wafted towards us,” which presents a red Colossus out of Goya striding across a light blue river beneath an orange sky — while also fading into the surface.

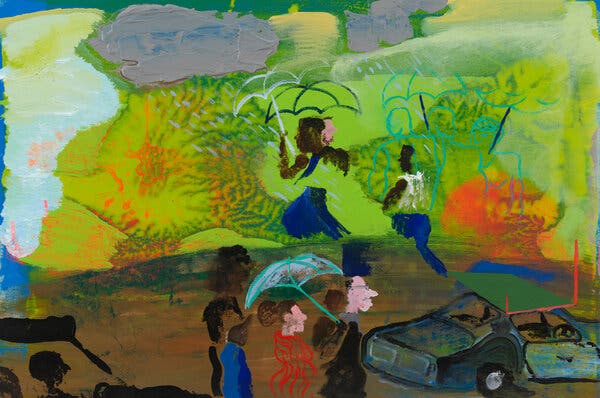

In contrast, a work titled “It has to rain before you can see where all the leaks are at,” suggests a contemporary street scene involving several figures, three umbrellas and two cars while around them a series of greens evoke stormy weather and a verdant park, while some kind of unexpected chemical interaction of paint creates patterns implying plant growth. Further down West 26th Street, at Galerie Lelong, is the magical first show of Ficre Ghebreyesus, an Eritrean-born painter, who is sadly no longer with us.

Through Oct. 17 at Marianne Boesky Gallery, 507 West 24th Street; 212-680-9889, marianneboeskygallery.com.

Gina Beavers’s latest garishly painted reliefs focus on the unending presence of the female face and body in art and advertising and run with it. They also show a deeply eccentric artist giving her all.

Ms. Beavers’s works bulge out from the wall in enlarged, often repeating forms that she covers with coarse but skillful brushwork, like van Gogh on steroids. Subjects include bright pink lips attended by tubes of lipstick; torsos flaunting bikini underwear styled with motifs from Picasso and Mondrian; and a hand with fake nails in the shape of Maurizio Cattelan’s taped banana.

In “Smoky Eye Every Step,” a repeating eye is progressively made up. The same happens to the half of the artist’s face, which is “made up” with a relief by Lee Bontecou. “People I admire: Mike Kelly, Ru Paul, Obama, Elaine de Kooning, Madonna,” offers a large single image of the artist’s face with five additional pairs of famous eyes. These works conflate all kinds of self-improvement and adornment projects: makeup, tattoos, cosmetic surgery and nail art as well as fandom and celebrity-worship. Their blaring billboard power from afar is countered by a squirm-worthy intimacy up close. In its own beauty-obsessed way, this is a beautiful show.

Two painting shows not to miss lie within a few steps of Ms. Beavers’. Just doors to the east, at Lehmann Maupin, the Brazilian twins Osgemeos continue to convert their popular graffiti style — centered on tall, yellow, thin-limbed figures with platter-like heads who are often seen against patterns of gemlike color — into portable works more suitable for private collectors. Close by on the west, Amy Sillman’s debut show at Gladstone continues her quest, in paintings, large drawings and smaller images of flowers, for an individual abstract style with some of the best paintings of her career.

Through Oct. 31 at Hales Gallery, 547 West 20th Street; 646-590-0776, halesgallery.com.

Abstract paintings of a more historical vintage feature in Virginia Jaramillo’s exhibition at Hales. The artist, 81, is currently having her first museum exhibition of her geometric curvilinear paintings of 1969-1974 at the Menil Collection in Houston. The Hales exhibition picks up in 1975, when Ms. Jaramillo detoured into a delicate, almost disembodied form of stain painting. Layering together thin washes of color, she created subtle shifts in tonalities, and shapes within shapes that, while barely there, verge on visionary. Pure color alternates with suggestions of skies and landscapes, as in “Thira,” in which veils of pale brown insinuate a mirage of graceful rock formations hovering in mist. (Also on West 20th Street, the latest abstractions of Odili Donald Odita at Jack Shainman offer a geometric retort to Ms. Jaramillo’s fluidity, and show this artist, whose bracingly optical patterns are influenced by African textiles, expanding his vocabulary.)

Through Oct. 17 at David Zwirner, 525 and 533 West 19th Street; 212-727-2070, davidzwirner.com.

The first show of the Belgian-born, New York-based painter Harold Ancart at David Zwirner has a standard look. Its extra large paintings seem tailored to the large space. The subtext: you can’t afford these paintings, nor could you fit them in your house, anyway. But have fun looking — and you very well may. These are nothing if not attractive paintings.

Two 30-foot triptychs — a mountainscape and a seascape — seem destined to hang in corporate lobbies; they are overbearing public art. Less dwarfing are 10 still large Popish paintings of giant trees: masses of usually dark blue and green foliage and thick woody trunks set against skies of pink, blue or orange. In one, the leaves are fiery orange, the trunk becomes a building and the combination can evoke one of the burning towers of the World Trade Center on Sept. 11.

The best thing about these works are their distinctive surfaces. Mr. Ancart has replaced paint and brushes with oil stick applied in thick but flat, implacable layers that seem the result of very arduous drawing processes. Given that every painter must, to some extent, reinvent the materials of the medium, Mr. Ancart has got the hard part out of the way. But he should resist the urge to go big. It’s only going to make everyone a lot of money.

There’s not much agreement among these 15 shows about what painting should be right now. But they all have their own challenging energy and clarity. They portray the medium as a Tower of Babel, where artists invent their own languages by combining bits of traditions with things only they know. That’s quite a healthy situation.