Ron Gorchov, an abstract painter widely known for vividly colored, saddle-shaped canvases that curved away from the wall and gently warped the viewer’s perception, died on Aug. 18 at his home in Red Hook, Brooklyn. He was 90.

His death was confirmed by his Manhattan gallery, Cheim & Read. His family said the cause was lung cancer.

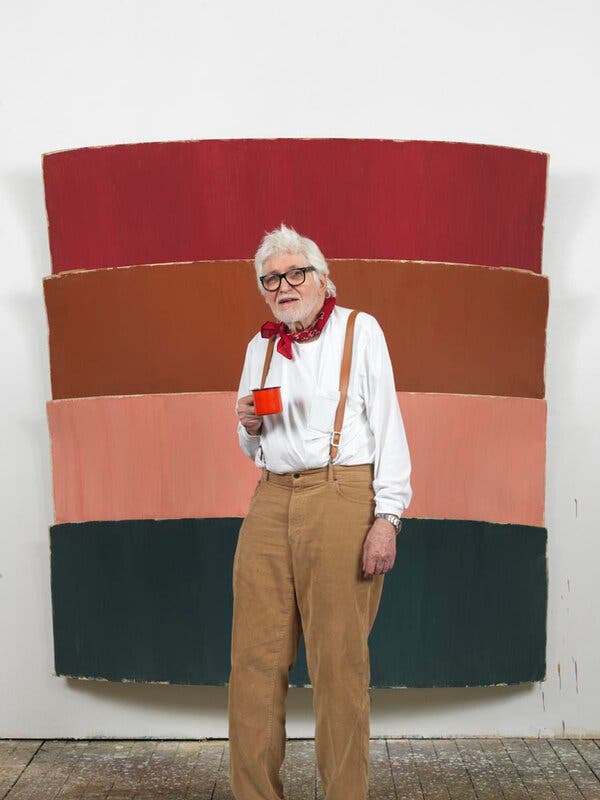

A tall, solidly built man with a kindly face, Mr. Gorchov may have been the closest thing the New York art world had to a gentle giant in the late 20th century. He was soft-spoken and approachable, with a relaxed manner. In a 2006 interview with the art newspaper The Brooklyn Rail, he said his paintings came not from angst but from “reverie, and luck” and “out of leisure.” He attracted a broad following among younger painters, particularly in the last 15 years, when his work enjoyed a new prominence.

Mr. Gorchov was one of many painters who, in the 1970s, ignored rumors of the medium’s death while rejecting the scale, slickness and purity of Minimalist abstraction. These artists personalized abstract painting in all sorts of ways, for instance by adding images, working small or using quirky geometry. Several of them, including Ralph Humphrey, Robert Mangold, Richard Tuttle, Elizabeth Murray, John Torreano, Lynda Benglis, Marilyn Lenkowsky and Guy Goodwin, put an idiosyncratic, intuitive spin on a Minimalist staple — the shaped canvas.

Mr. Gorchov did, too. But he was older, and his art blended some of the grandeur of 1950s Abstract Expressionism with the more skeptical, humorous attitudes of the ’70s.

Maurice Ronald Gorchov was born on April 15, 1930, in Chicago to Herman Noah and Grace (Bloomfield) Gorchov. His father was an entrepreneur. His mother was an artist who had studied painting at the Art Institute of Chicago. She “began to give me ideas about art pretty early” Mr. Gorchov said in an unpublished 2017 interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries in London.

Mr. Gorchov began taking Saturday art classes at the Art Institute when he was 14 and later night classes there. When he was 15 he began working as a lifeguard, his 6-foot-4 frame enabling him to pass for 18, the required age. At 18 he decided to become a painter.

Mr. Gorchov’s peripatetic higher education never yielded a degree. From 1947 to 1951 he studied at the University of Mississippi in Oxford; Roosevelt College (now Roosevelt University) in Chicago, where he played football; the Art Institute; and finally the College of Fine and Applied Arts at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

He married Joy Lundberg, an opera singer, in 1952 and relocated to New York the next year, landing a job as a lifeguard and swimming instructor. He soon met the Abstract Expressionist Mark Rothko in a bar, and they became friends. He also became close with John Graham after seeing an exhibition of his paintings of voluptuous cross-eyed women at the prominent Stable Gallery in 1954. Over the next few years Mr. Gorchov started working in a richly colored version of the style known as abstract surrealism.

His first marriage ended in divorce, in 1960, as did his subsequent marriages to Karen Chaplin, in 1967, and to Ms. Lenkowsky, in 1975. He is survived by his wife, Veronika Sheer, whom he married in 2012; his son, Michael; and his daughter, Jolie, from his first marriage.

Mr. Gorchov enjoyed early success, starting in 1960 with his first solo show, at Tibor de Nagy Gallery, known for spotting young talent. Reviewing that show in The New York Times, Dore Ashton compared the “sumptuous profusion” of his palette to that of the revered painter Arshile Gorky. Mr. Gorchov’s work was included in the 1961 Pittsburgh International Exhibition of Contemporary Painting and Sculpture (renamed the Carnegie International in 1982) and had two more solos at Tibor de Nagy, in 1963 and 1966.

By the mid-1960s he had grown dissatisfied with painting on a flat, rectilinear surface and began to seek “a more intentional form that would create a new kind of visual space,” as he told the artist Ray Smith in an unpublished interview in 2014.

It took several years of trial and error, during which Mr. Gorchov all but stopped exhibiting. From 1966 to 1971 he finished only one painting, the 10-by-12-foot “Mine,” which curved slightly inward across its middle, bent forward at each corner and featured blurry flamelike motifs in red, yellow and blue reminiscent of Rothko. Although it was beautiful, Mr. Gorchov deemed “Mine” too close to traditional. His experiments continued.

In 1971 he started stacking multiple canvases with gently curved, round-cornered tops that he called “half saddles” into towering, free-standing but one-sided pieces, sometimes arranged to resemble gateways. Their large size, he said, made it easier to see what was wrong with them. He finally succeeded in making a “whole” saddle-shaped stretcher in 1972, exhibiting the resulting paintings for the first time at the Fischbach gallery in 1975. It was his first solo show in New York in nine yearMade in different sizes and proportions, this structure would serve him for the rest of his life. The paintings were altogether odd, at once awkward and delicate. With their stretchers partly visible and the close-fitting, raw-edged canvas stapled to the front, they held no secrets, offering themselves to the viewer as a single, curving, almost enveloping layer of brushwork and color.

The painting process was immediate and unfinished, starting with a color or color mixture applied in thin, downward strokes that could suggest rivulets of water, with drips accumulating at the bottom edge. To this surface were added a pair of marks, often but not always matching in shape and color. They could suggest eyes, beans or islands, but mainly they intimated the body’s symmetry and implied that they might have been painted by someone with a brush in each hand — which they sometimes were.

At the time, several writers called Mr. Gorchov’s paintings “primitive,” but he preferred “rudimentary.” They took painting back to a primal state and a set of motifs that changed only a little, flirting with repetition but rarely succumbing to it. In this his work recalled some of the Abstract Expressionists, especially Clyfford Still.

In the 1980s and ’90s Mr. Gorchov dropped from sight again, showing only infrequently in New York until 2005, when his first solo show in 13 years was staged by Vito Schnabel, a young art dealer (and son of the painter Julian Schnabel). That show publicly displayed Mr. Gorchov’s “Mine”for the first time in 28 years; it also alerted a new generation of painters to his work.

In 2006 “Double Trouble,” a survey of Mr. Gorchov’s work, was seen at MoMA PS 1. Mr. Schnabel continued to work with Mr. Gorchov after Cheim & Read began to represent him in 2011, helping his work become more visible in Europe.

Over the years, the pairs of marks became more dissimilar in color and shape; sometimes, especially in the 1980s, they increased in number and complexity, expanding into slurry, cursive gestures reminiscent of the artist’s early surrealist abstractions. They constitute some of Mr. Gorchov’s most elegant and suggestive works, as proved by his most recent show in New York, “Ron Gorchov: At the Cusp of the ’80s, Paintings 1979-1983,” at Cheim & Read in the fall of 2019.

Mr. Gorchov’s work is represented in the collections of several museums, including the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Guggenheim Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Yale University Art Gallery and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City.