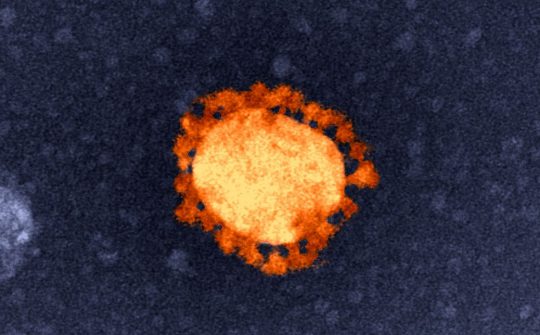

An image of the corona virus responsible for causing the disease COVID-19. Image: CSIRO.

An architecture researcher at the University of SA suggests that historical design of health and medical buildings could inform safe design in future.

Dr. Julie Collins, collections manager at the University of South Australia’s Architecture Museum, began researching her book on the history of architecture for medical buildings well before the globe was engulfed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Newly released as the pandemic rages, The Architecture and Landscape of Health: A Historical Perspective on Therapeutic Places 1790-1940 finds striking parallels with the approach to containing historical outbreaks of disease.

“When you look at health crises like the tuberculosis pandemic in the 1800s, before we had pharmaceuticals and biomedicine, really ‘place’ was one of the only ways we could prevent and counter the spread of communicable diseases,” Dr. Collins said.

“The approach was to isolate ill people in dedicated sanatoria that provided fresh air, good nutrition, rest and exercise, all under medical supervision.

“Then when we developed pharmaceuticals – these kind of magic bullets cures – a lot of those ideas fell by the wayside, which is a pity, because as we can see now, they are still relevant to the isolation principals we’re falling back on in the absence of other effective treatments.”

Dr. Collins has found in her research that a range of design principles were informed by sound medical science that helped protect against epidemiological threats that were poorly understood at the time, but still hold true today — especially in a Covid-19 affected world.

She said that though many of these design principles may be taken for granted, they have not necessarily been adhered to as scientific advancements reduced the need for quarantine facilities.

“The architects of these places realised the importance of ventilation, windows that could be opened to allow fresh air and natural light, as well as the importance of keeping distance between people and providing proper sanitation,” she said.

Dr. Collins said that built environments have consistently evolved in response to challenges of illness and disease, an approach that could inform safer design of workplaces and common spaces into the future.

“For example, following the rapid urbanisation of the population during the Industrial Revolution, we began building city parks, both as ‘urban lungs’, but also through the recognition that mental health was aided through exposure to nature and exercise and social interaction,” she said.

“Also, the whole modernist movement in architecture and design – the clean lines, open spaces, minimalist styles – developed as an extension the principals of hygiene and sanitation that guided early hospitals and public health buildings.

“Coronavirus might lead us to re-examine aspects of many workplaces, as well as the areas associated with them – what we call third places – the coffee shops and other small social places we use during our working lives.”

The Architecture and Landscape of Health: A Historical Perspective on Therapeutic Places 1790-1940 has been published by Routledge and is available now.

Stay up to date by getting stories like this delivered to your mailbox.

Sign up to receive our free weekly Spatial Source newsletter.