IN AMERICA IN the 1960s, the museum that showcased the latest and best contemporary art was located, predictably enough, in New York, but it wasn’t the Guggenheim, the Whitney or the Museum of Modern Art. Instead, the epicenter of the shock of the new was the modestly endowed upstart that art-world insiders affectionately called “the Jewish.”

Housed on upper Fifth Avenue in a Renaissance Revival mansion with a Modernist annex, the Jewish Museum is where the dealer Leo Castelli discovered the work of Jasper Johns, where the 37-year-old Robert Rauschenberg had his initial retrospective and where the 1966 exhibition “Primary Structures” caught and popularized the cresting wave of Minimalist sculpture. It was at the Jewish that New York museum audiences were introduced to such diverse artists as Mark di Suvero, Richard Tuttle, Joan Mitchell, Tony Smith, Robert Irwin, Grace Hartigan, Larry Rivers, Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Carl Andre, Dan Flavin and George Segal. And it was there, too, that Helen Frankenthaler, Kenneth Noland and Ad Reinhardt received their first solo museum shows. “It was the most radical place in New York City, the only place you could see seriously installed contemporary art,” says the artist Mel Bochner. “These shows were groundbreaking and established the possibility of a future. Important things were being discussed at the Jewish Museum that weren’t being said elsewhere.”

To understand how a museum controlled by the tradition-bound Jewish Theological Seminary came to spearhead the artistic avant-garde, it is necessary to appreciate the social status of Jewish Americans in the postwar years, the minor position of contemporary art at that time and the role played by a few inspired, ambitious curators. In 1947, the Jewish Museum expanded out of the seminary’s library annex, which contained a collection of historic Judaica, and moved into the mansion given to it by Frieda Schiff Warburg, who was the wife and daughter of renowned financiers. At the time, the few Jews welcomed as trustees at elite cultural institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Art Institute of Chicago came from wealthy, established German Jewish (as opposed to Eastern European Jewish) families — and like the board members, the art that those museums collected needed to have passed the test of time. Even the avowedly “modern” museums in New York hesitated to display the achievements of young American artists.

Many of the collectors who flocked to the less snobbish and more affordable precincts of contemporary art were Jewish — among them, Robert and Ethel Scull, who ran a New York taxi business and had a preternatural eye for the contemporary, and Frederick and Marcia Weisman, who lived in Los Angeles and had made a fortune in real estate. Another enthusiast was Vera List, the wife of Albert List, a self-made millionaire industrialist of Romanian Jewish heritage who was on the board of the Jewish Theological Seminary. When Vera proposed donating a sculpture, “The Procession,” by Elbert Weinberg, to the Jewish Museum in 1957, the trustees hesitated. “The Procession” was a figurative piece that represented men carrying a Torah and a menorah, rendered in Modernist angles. Some board members questioned whether the acquisition was permissible, considering the Second Commandment prohibition of graven images. Eventually, loath to rebuff the generosity of a significant benefactor, the board approved the donation.

In 1962, Vera List became the chair of the Jewish Museum’s newly constituted board of governors, which declared its allegiance to “the work of younger or otherwise unacknowledged” artists. The senior staff resigned in protest, but the shift was less abrupt than it might seem, because Stephen Kayser, the exiting de facto director, had also championed contemporary art as a way of attracting visitors. For a 10th-anniversary show in 1957, with advice from the distinguished art historian Meyer Schapiro, Kayser mounted the far-reaching and farsighted “Artists of the New York School: Second Generation,” at which Castelli first laid eyes on Johns’s 1955 painting “Green Target.” Intrigued, Castelli visited Johns’s studio, reacted with messianic fervor to what he was shown and in early 1958, presented the show that launched Johns’s fame and changed the course of postwar American art. By sparking the interest and sculpture donation of List, “Artists of the New York School” also altered the trajectory of the Jewish Museum — and placed it on a path on which it would help predict and shape the movement of contemporary art for years to come.

KAYSER’S DEPARTURE amounted to a change of emphasis and style. A specialist in Jewish art, he had emigrated from Germany in 1938. “Stephen Kayser was an old-fashioned gentleman,” recalls Tom Freudenheim, who was a curator at the museum in the early ’60s. “He still had his heavy accent. He was of that generation of people who had a formality about them.” His successor, Alan R. Solomon, was a Harvard-trained academic and curator who had founded the art gallery at Cornell University. “Alan Solomon was a quite sophisticated art historian who, as they say in the art world, happened to be Jewish,” Freudenheim continued. “He had very, very high standards, and he would absolutely not yield on them.” As Vera List put it in an oral history at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Kayser’s shows were “like a whisper,” and when Solomon came in, “he had much more space, and he wasn’t whispering; he was bellowing.”

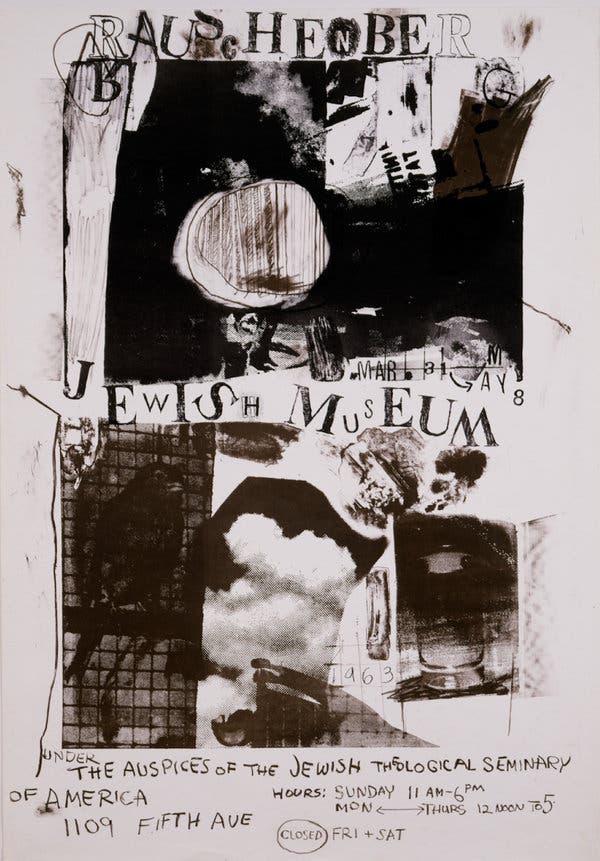

Solomon served as director for only two years, from July 1962 to July 1964. Despite the brevity of his career, he set the museum on its course. For his debut exhibition, in March 1963, he presented a Rauschenberg retrospective of paintings, transfer drawings and the three-dimensional “combines” that melded elements of both painting and sculpture. He followed with “Toward a New Abstraction” that summer, which provided an overview of hard-edge abstract painting and included the shaped canvases of Frank Stella and the monochromes of Ellsworth Kelly. His 1964 solo show of the 33-year-old Johns was even more magisterial than the Rauschenberg exhibition.

But it wasn’t just what he showed that would make Solomon a key figure in reshaping the mission of the modern art museum — it was when and how he showed it. “That was where Alan was really prescient,” Freudenheim says. “You might say he was the father of the midcareer retrospective.” Solomon treated his contemporaries like old masters, applying the most rigorous expectations to shows of artists who were still in their 30s. Bochner, who worked as a guard at the museum in the early ’60s, was once accosted by Solomon in a gallery that was displaying prints by Marc Chagall. “He looked at me and said, ‘That print is crooked,’” Bochner recalls. “I said, ‘I don’t know, sir, it looks OK to me.’ He had a tape measure in his pocket. He took it out and measured. It was one-sixteenth of an inch off. He said very imperiously, ‘Please correct that.’ He put the tape back in his pocket and walked off.”

Acknowledging what he termed in his foreword to the Johns catalog to be the museum’s “two- fold policy,” Solomon also staged shows, like the Chagall prints, with a clear Jewish content. He recognized that the museum was the subsidiary of a seminary. He was even able, in a 1963 show of modern American synagogue architecture, organized by Richard Meier, to perform the neat topological trick of combining the contemporary and the Jewish into one. But the tension between some board members’ interests and Solomon’s own lingered. In an often told tale, the widow of an eminent seminary scholar asked at the Rauschenberg opening whether the artist was a Jew. Told that he was not, she exclaimed, “Thank God!”

Rauschenberg would be chosen to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale the following year, in a presentation organized by Solomon and the Jewish, and would win the show’s grand prize in painting. But Solomon spent so much time in Italy that the seminary board lost confidence in him. Nonetheless, the appointment of Sam Hunter as his successor in 1965 only affirmed the museum’s commitment to the avant-garde. During his tenure, Hunter organized retrospectives of Ad Reinhardt, Philip Guston and Max Ernst. His signature achievement, however, was recruiting from MoMA as a senior curator Kynaston McShine, the witty, opinionated scion of a distinguished Black Trinidad family, whose exhibitions would herald some of the most important trends in contemporary art. McShine was at the Jewish from 1965 to 1968 (the last year as acting director), a break from his otherwise lifelong tenure at the Modern. But in that short sojourn, he contributed greatly to the Jewish’s mythology. Inspired by the sizable main exhibition gallery in the new wing, he staged “Large Scale American Paintings” in the summer of 1967, displaying canvases of 23 American artists, including Al Held’s truly monumental “Greek Garden,” a geometric study in acrylic, which stretches 56 feet long. (In June 1965, the museum had displayed in the same room James Rosenquist’s 86-foot-long “F-111,” a Pop Art depiction of the titular bomber plane, and a recent purchase of the Sculls’.) Earlier that year, McShine mounted the first American museum retrospective of Yves Klein, already a legend not even five years after his premature death.

The show for which McShine is best remembered — and which is one of the most celebrated exhibitions of the late 20th century — is “Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors,” from 1966. McShine assembled works by East Coast, California and British sculptors, early in their careers, who shared what we now call a Minimalist aesthetic. Here for the first time together were artists like Carl Andre, Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Larry Bell, Anne Truitt, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Morris and Ronald Bladen, who used various materials (painted steel or aluminum, colored plastic, coated glass) in different ways (structured repetition of prefabricated units, heroically scaled steel) but shared an interest in machine-made objects, smooth planes of vibrant color and the removal of the sculpture from a pedestal. “It had tremendous impact because it was really the first show including those artists,” says the dealer Paula Cooper, who went on to represent many of the show’s contributors at the eponymous New York gallery that she founded in 1968. “I think it was the beginning.”

“Primary Structures” had its eye trained so thoroughly on the future that it would take years for its importance to be recognized. Judy Chicago, then known as Judy Gerowitz, exhibited “Rainbow Pickett,” a sequence of six brightly painted wooden beams that leaned against the wall. “I got nowhere with a lot of that big sculpture,” she says. “My male peers would get picked up and be on the choo-choo train, and I had to constantly start over again. After a decade and a half of that, I changed direction.” Robert Grosvenor, who installed “Transoxiana,” a 31-foot-high V-shaped sculpture of painted wood and steel that was destroyed after the exhibition, says the show “had no impact whatsoever” on his career. For Hunter, too, “Primary Structures” did little to help his standing at the museum. He was forced to resign in October 1967.

Hunter’s replacement, Karl Katz, who had been a curator at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, had a reputation as being “open to pretty much anything,” says the curator Susan Tumarkin Goodman, who in 1970 organized “Using Walls,” with a group of artists — the roster included Richard Artschwager, Lawrence Weiner, Richard Tuttle, Sol LeWitt and Bochner — who drew and painted directly onto the museum’s walls. But Katz’s daredevil spirit would also indirectly end the museum’s improbable run as the primary promoter of the avant-garde. His 1970 exhibition “Software: Information Technology and Its New Meaning for Art” was a flawed but visionary look at the impact of computer science on art. Everything in the show — the exhibitions, the performing artists — ran on programmed instructions or were issued from a prescribed system. Those artists included Vito Acconci, John Baldessari, Allan Kaprow, Joseph Kosuth and Nam June Paik, most of whom were still largely unknown to the general public. The day before “Software” opened, Katz gave a tour to the seminary chancellor, Rabbi Louis Finkelstein, and a representative of the Smithsonian, which wanted to stage the show and therefore defray some of its costs. The three men viewed Nicholas Negroponte’s installation, “Seek,” in which a computer-controlled claw moved 2,000 metal-coated plastic cubes of a maze navigated by gerbils. Then they advanced to a video recording by Les Levine. As Katz recalls in his memoir, all was fine until they got to the footage that depicted the artist stark naked in the company of two equally unclad women. The rabbi sputtered in furious disbelief.

“I think, Mr. Katz, that this is the end,” he said.

And it was. A fire at the Smithsonian, coupled with technical failures in the challenging show, led to the cancellation of the Smithsonian showing, and “Software” finished at least $50,000 over budget. The combination of salaciousness and shortfall was insurmountable, and the seminary declared it would no longer subsidize a program that was not “basically Jewish.” Katz submitted his resignation the next day.

THAT SHOULD HAVE been the final chapter in the museum’s role in the vanguard. By 1970, Solomon’s program was becoming everybody’s program. It was no longer risky for prestigious museums to present contemporary art because, commercially and critically, contemporary art was becoming prestigious. Two years after returning to MoMA in 1968, McShine mounted “Information,” a survey of conceptual art that featured such Jewish Museum exhibition alumni as Andre and Daniel Buren. In 1980, the Whitney purchased Jasper Johns’s “Three Flags” for $1 million, a record at the time for a living artist. (A “Flag” painting the size of a place mat sold at auction in 2014 for $36 million.) In a generation, contemporary art had gone from being viewed with suspicion and slight distaste to being an asset, its acquisition an announcement of both one’s taste and one’s wealth. So, too, had the Jewish’s once radical commitment to the midcareer retrospective gone from daring to de rigueur; the show quickly became a museum-menu staple.

Then there was the fact that Jewish people no longer had to start their own museums. After decades of exclusion, Jews, including those from Eastern European backgrounds, began joining the boards of the major arts institutions. Today, Daniel Brodsky is the chair of the Metropolitan, Leon Black is the chair of MoMA and Leonard Lauder is the chairman emeritus and éminence grise on the board at the Whitney.

The culture at large had finally caught up with the one the Jewish Museum had helped create. And yet, improbably, the Jewish had one last prediction to make. In 1972, the museum appointed as its director Joy Ungerleider-Mayerson, a specialist in biblical archaeology. Under her stewardship, the institution began to concentrate on Jewish themes and Israeli artists; one of her first tasks as director was to negotiate the acquisition of 600 ancient artifacts from Israel, and one of the major shows during her tenure, from 1975, was called “Jewish Experience in the Art of the 20th Century.” The museum went, in other words, from advancing provocative art to concentrating on identity culture. And viewed that way, the Jewish Museum was still on the cutting edge. The Studio Museum in Harlem, which exhibits African-American art, opened in 1968; El Museo del Barrio, which focuses on Latino culture, was founded the next year. Today, the questions and tensions that surround and are informed by identity culture — who am I and how do I fit within the society around me? — also provide an engine for contemporary art itself.

Under its current director, Claudia Gould, who has a background in contemporary art, the museum straddles its dual legacies. It continues to mount innovative, sometimes forward-thinking shows, such as 2018’s survey of Martha Rosler, the pioneering feminist and video artist whose politically charged work from the ’60s feels newly relevant today. With exhibitions like “Marc Camille Chaimowicz: Your Place or Mine,” staged that same year, the museum looked anew at an artist whose work had previously been considered decorative. It is, however, still grappling with internal and external debates over whether the museum is “too Jewish” or “not Jewish enough.” In 2018, it installed an ongoing exhibition of Jewish ceremonial objects integrated with artworks from its collection. Some felt the show was facile and unscholarly; others found it adventurous: an effort to interest younger visitors in objects they might otherwise ignore.

In the summer of 2022, the Jewish Museum will present a survey of the New York art scene from 1962 to 1964. During these years, Andy Warhol opened his Factory studio in Midtown, Donald Judd laid out his artistic philosophy in an essay called “Specific Objects” and Pace Gallery, now one of the largest in the world, moved from Boston to Manhattan. And then there was the Jewish Museum itself — pushing the idea of what a museum could and should be in different and previously unheard-of directions.