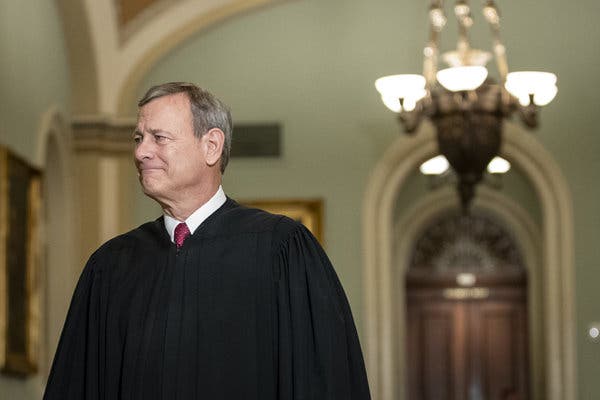

What is up with Chief Justice John Roberts? Has he been cowed by political pressure to move left? Is there a method to his apparent maddening pattern of trading off conservative opinions with liberal ones?

The chief justice has sided with the Supreme Court’s liberal justices on some of the biggest cases of the term, like decisions to invalidate the Trump administration’s effort to rescind the DACA program and Louisiana’s abortion-provider regulations. In others, he has stuck with the conservatives.

Chief Justice Roberts’s voting pattern certainly fails to conform to a predictable ideological pattern. But there is a pattern nonetheless. He is a conservative justice, but more than anything else, he is a judicial minimalist who seeks to avoid sweeping decisions with disruptive effects.

This has been the hallmark of his jurisprudence since he joined the court in 2005. And while there are significant exceptions (most notably, Shelby County v. Holder, which invalidated a major component of the Voting Rights Act), Chief Justice Roberts’s anti-disruption jurisprudence has become more pronounced the longer he has been on the court.

As a judicial minimalist, Chief Justice Roberts seeks to resolve cases narrowly, hewing closely to precedent and preserving status quo expectations. If a litigant seeks an outcome that will transform the law or produce significant practical effects, his vote will be harder to get. At the same time, he takes a strict view of “justiciability” — that is, whether a case should be in federal court at all. He is also reluctant to bless new avenues of litigation for those who seek to use the courts to drive public policy

He is generally reluctant to overturn decisions or to strike down federal laws. Thus he often reads precedents narrowly or construes federal statutes in ways that will avoid constitutional problems. Since he became chief justice, the Supreme Court has overturned its own precedents and struck down federal laws at a much lower rate than it did under Chief Justices Earl Warren, Warren Burger or William Rehnquist.

Where the chief justice concludes a statute is unconstitutional, his aversion to disruptive decisions leads him toward narrow remedies, including an aggressive approach to the doctrine of severability, under which the court excises as little of a law as possible to cure a constitutional defect.

For instance, after he found that the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion was unconstitutionally coercive on state governments in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, his remedy was to make the expansion optional, removing the coercion, while leaving the rest of the law in place.

These impulses have been on clear display in the chief justice’s decisions this term. In Seila Law v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, for example, he concluded Congress had unconstitutionally insulated the bureau’s director from presidential control by barring removal without cause. His decision remedied this constitutional flaw simply by eliminating the limitation on removal, while leaving the bureau’s regulations and enforcement actions intact.

This approach, he explained, would minimize the “disruption” of the decision; it also matches a strikingly similar remedy he ordered in 2010 in Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (that case involved a challenge to the constitutionality of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, which established the board and sought to reform corporate America after the Enron and WorldCom accounting scandals). In addition, he made clear this holding applied only to the handful of agencies with an equivalent structure, and not to other independent agencies.

Chief Justice Roberts has hewed closely to precedent as well. In June Medical Services v. Russo, he voted to strike down Louisiana regulations governing abortion providers because they were virtually identical to ones in Texas that the court had struck down just four years ago. Although he disagreed with the court’s earlier decision, he explained that the need for the court to follow precedent and decide like cases alike required this result.

And in Ramos v. Louisiana, he voted against requiring unanimous jury verdicts in state courts under the Sixth Amendment, as he believed this would have required overturning a 1972 precedent, imposing ‘a potentially crushing burden on the courts and criminal justice systems of those States.’” Notably, this is the only dissenting vote the chief justice has cast thus far this term.

His aversion to disruption may have been most plain in his opinion rejecting the Trump administration’s DACA rescission. The administration has the authority to rescind DACA, Chief Justice Roberts explained, but it failed to account adequately for the “reliance interests” of those who depended upon the program, including not just DACA recipients but their families, employers and communities.

Much as in King v. Burwell, where the chief justice was unwilling to accept an interpretation of the Affordable Care Act’s text that risked depriving millions of Americans of subsidized health insurance, he was unwilling to greenlight a sloppy Trump administration effort that would have put thousands of law-abiding noncitizens at risk of deportation.

Even where Chief Justice Roberts has been responsible for disruptive opinions, he appears to have done so reluctantly. Four years before the Shelby County decision on the Voting Rights Act, he wrote a majority opinion in Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District No. 1 v. Holder, adopting an implausible interpretation of the act’s text so as to fend off a constitutional attack.

Writing for an 8-1 court, he justified stretching the statute’s text because of “underlying constitutional concerns” about Section Five (the act’s requiring of certain states to get federal approval of changes in their election laws) — concerns he likely hoped Congress would fix before another such challenge reached the court. Congress’s failure to act, the chief justice would write in Shelby County, left him “no choice” but to reach the underlying constitutional question. Even if you find the explanation unpersuasive, you can see the gravitational pull of his minimalist ethic in his approach.

In his confirmation hearing, Judge Roberts got attention for saying that “judges are like umpires” because they “don’t make the rules, they apply them.” Most commentators dwelled on his suggestion that deciding cases was like calling balls and strikes, but perhaps they missed the real point: “Nobody ever went to a ballgame to see the umpire,” he explained.

In much the same way, Chief Justice Roberts does not like the focus to be on the courts. He would prefer it if the major issues of the day were resolved in Congress or at the ballot box.

This is a noble sentiment, but it may also be a bit outdated and naïve. “There is hardly any political question in the United States that sooner or later does not turn into a judicial question,” observed Alexis de Tocqueville in 1835. This is only more true today. Whether Chief Justice Roberts likes it or not, hard calls in high profile controversies keep coming his way.

Jonathan H. Adler, a professor at the Case Western Reserve University School of Law, is the editor of the books “Business and the Roberts Court” and “Marijuana Federalism: Uncle Sam and Mary Jane.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.