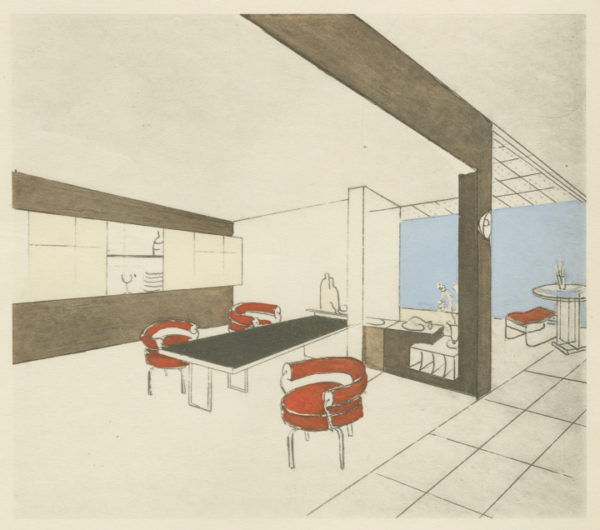

PARIS — In 1927, two years after studying furniture design at the Ecole de L’Union Centrale des Arts Decoratifs in Paris, Charlotte Perriand moved into a photographer’s attic studio on Place Saint-Sulpice and converted it into her apartment, in which she designed everything. The open-plan space, divided by low stainless-steel storage cabinets and shelves, featured rotating “swivel” armchairs and stools made from chrome tubular frames and black or blood-red leather; a wall-mounted extendable dining table made from steel and rubber that could seat up to 11 people; and a steel, aluminum, and glass bar and card table with snooker-pocket drink holders, known as “Bar sous le Toît” (the bar under the roof).

It was a radical departure from traditional interior design. No walls or doors separated rooms. The furniture’s style was neither Art Deco nor decorative Beaux-Arts (the two dominant aesthetic movements in France at the time), and Perriand used industrial techniques — welding, folded sheet metal, mechanical hinges and screws — to make it. Later that year, the 24-year-old’s designs appeared at the Salon d’Automne and were praised by the press, as well as by Le Corbusier, who offered her a job as his design associate. (He had rejected her application a few months earlier with the words: “we don’t embroider cushions here.”)

A reconstruction of Perriand’s first apartment is on display in the magnificent and comprehensive exhibition Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, which showcases the avant-garde designer’s contribution to 20th-century architecture and interiors over seven decades. One of the best aspects of the show is that visitors can walk into mock-ups of the spaces she created, sit on the furniture, and feel the materials. “We want you to experience her work, rather than just look at it,” co-curator Sébastien Cherruet told me. This was important to Perriand. “Furniture design is based on logical principles,” she explained in 1928 (reprinted on a wall text). “Needless prettifying must be avoided. Its beauty must come from the rational arrangement of its parts.” This philosophy extended to her own appearance, too: “I had a street urchin’s haircut,” she writes in her memoir Charlotte Perriand: A Life of Creation (1998), and she wore a trademark necklace made of chromed copper ball bearings: “a symbol of my adherence to the … machine age.”

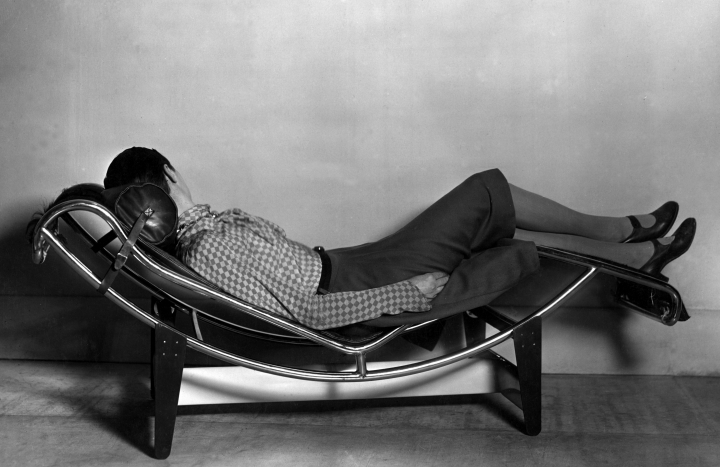

While working with Le Corbusier and his cousin, Pierre Jeanneret, for 10 years, Perriand advanced her vision of modern living. She designed innovative, quietly effective furniture for their architectural projects, such as the cube-shaped “Grand Confort” chair and the adjustable “Chaise longue B306,” with its fur-covered sling seat, cylindrical leather headrest, and half-moon steel frame, which, as Perriand wrote in the patent documents, works “by a simple sliding motion and without any mechanical parts […].”

In the 1930s, Perriand turned to the seemingly haphazard geometry of nature for inspiration. Instead of metal and industrial materials, she used wood, woven fabrics, and cane. Her table tops were often fanned or curved and the table legs splayed so that anyone sitting at the end wouldn’t feel constricted. In 1938, for the office of Jean-Richard Bloch, editor of the Communist newspaper Ce Soir, she paired her swivel armchair from 1927 with a bespoke semi-circular “Boomerang” desk made from thick, rounded-off pieces of wood; this design allowed Bloch to orient himself toward several staff members gathered around him. Suspended underneath the desk, on one side, is a teal filing cabinet, and on the other, a small wooden cupboard for Bloch’s telephone so that nothing would clutter the expansive sweep of the desktop.

Alongside this, Perriand designed a minimalist coffee table with three thin cylindrical wooden legs arranged in a triangle formation. The black top — inset into a narrow wooden frame — is decorated with two white engravings by Pablo Picasso (including a frenzied horse and its armored, reptile-like rider) and two by Fernand Léger (shaded honeycomb shapes and spirals). It is a striking example of how design, architecture, and art were always synchronized in her mind and work.

Perriand’s connection with the Communist Party went beyond furniture. Her 16-meter-long (over 50 feet) photographic mural “Poverty-Stricken Paris,” created for the Salon des Arts Ménagers in 1936, stretches across one of the gallery’s walls. Its collage of multicolored text and black and white images moves from criticizing the French government’s urban planning, Paris’s unsanitary living conditions, infant mortality rates, environmental problems, and the unfair treatment of women, to the possibility of a better future. Photos of wailing children, farming machinery, and hopeful crowds are overlaid with mottos, such as “unity is strength” and “liberate the country’s natural and cultural riches for the benefit of all.”

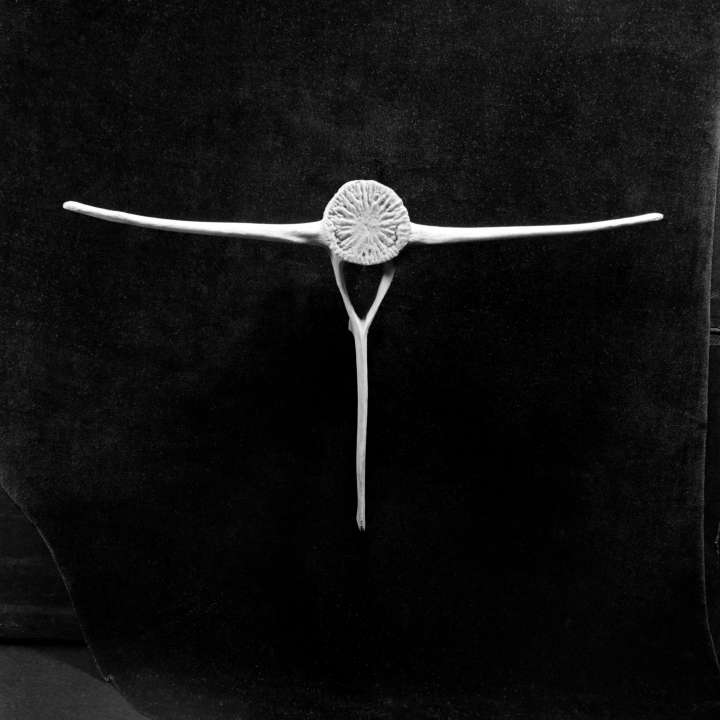

More of Perriand’s black and white photographs are displayed nearby. These are spectacular abstract, otherworldly close-ups of bones, skulls, flint, driftwood, drain pipes, crushed springs, and scrap metal. Most of them are spotlit and shot from above on a plain background, which creates the impression that they are floating in mid-air. Found objects (tree trunks and fossils, for example) also crop up in her interiors as readymade sculptures. “Jeanneret and I made weekend trips to the Normandy beaches,” she recalls in her memoir. “We would fill our backpacks with treasures: pebbles, bits of shoes, lumps of wood riddled with holes, horsehair brushes — all smoothed and enabled by the sea. We sorted them, admiring them, soaking them in water to give them more of a shine, and taking photographs. We called it our ‘art brut.’”

Mountains were another obsession. Perriand learnt to ski and mountaineer early on, and toward the end of the exhibition, we discover that she was instrumental in building the Les Arcs ski resort in the Alps in the 1960s and ’70s. As well as being the architect and urban planner, she created pre-fabricated, affordable bathroom and kitchen modules that could be craned inside the apartments and quickly connected together. She also developed a mobile mountain refuge (“Refuge Tonneau”). This small, spaceship-like dodecahedron hut is made from aluminum panels supported by a metal pole in the center and a metal frame on stilts, which could be embedded into the ground to provide stability. Each piece weighs under 90 pounds so that it can be carried, assembled, and disassembled easily. A coffin-shaped door and porthole window lead into a pinewood-lined cabin with a wood-burning stove, kitchenette, storage cupboard for skis (Perriand’s own skis have been placed here for the exhibition), and eight roll-out futon beds.

Other highlights include the interiors for Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, the wall-art and furniture for the offices and lobby of Air France in Tokyo, and Mondrian-like bookcases and storage units for the rooms in the Maison de la Tunisie at the Cité Universitaire in Paris. For this last project, Perriand picked the color scheme with the help of artists Sonia Delaunay, Silvano Bozzolini, and Nicholas Schöffer, and created removable steel dividers so that the shelving units could be turned into different surfaces (a large platform for sitting on, for instance, and a desk). That these projects, from over 50 years ago, haven’t aged shows just how iconic and contemporary Perriand was.

Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World continues at Fondation Louis Vuitton (8, Avenue du Mahatma Gandhi, Bois de Boulogne, Paris, France) through February 24.